WHEN THE EARTH BURNS, WHO GETS BURIED FIRST?

Climate change is not casteless. In India, caste decides who lives on the margins of survival. As the planet heats, Dalit and Adivasi communities face the harshest consequences.

Caste and Climate Change

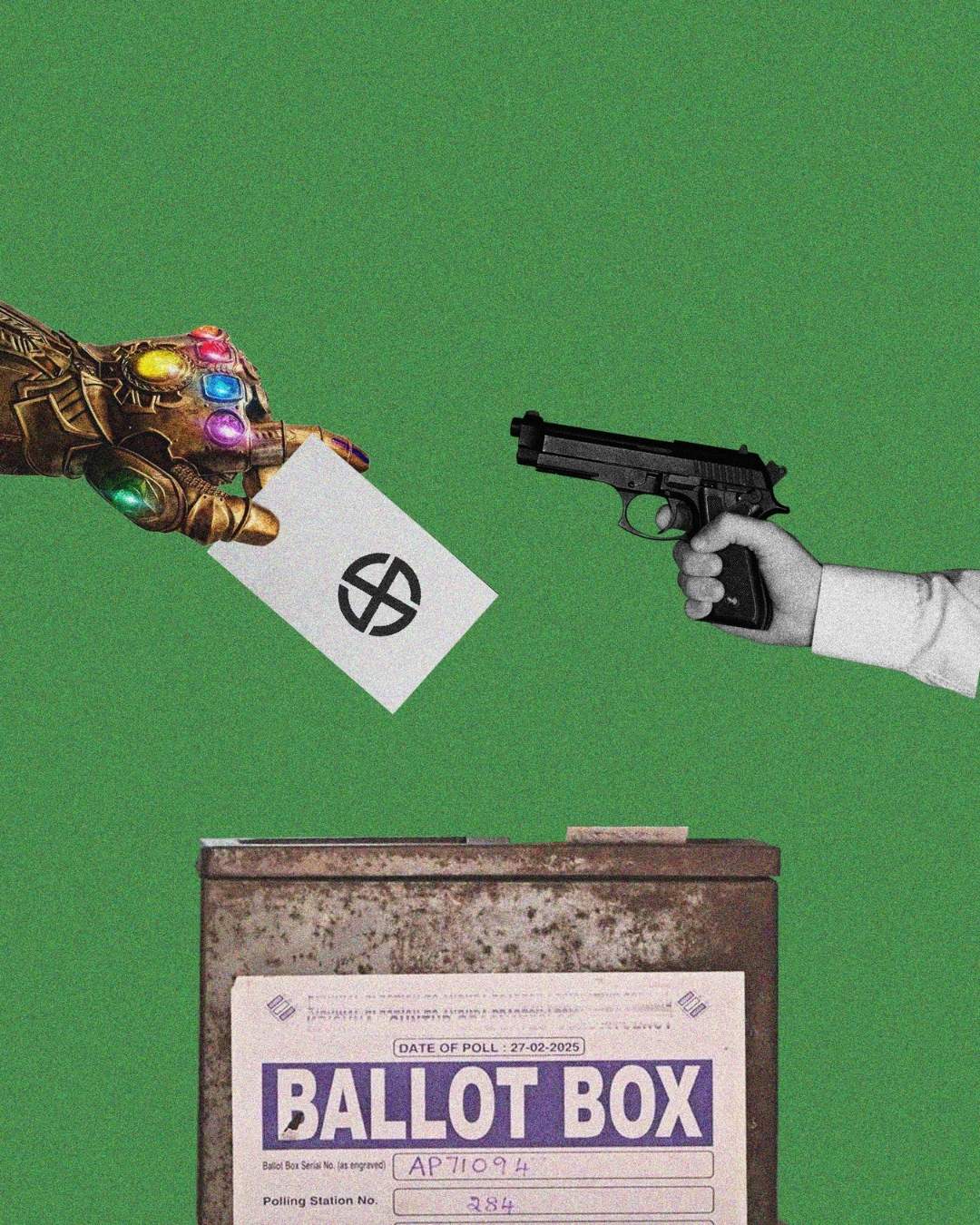

EVM “Vote chori”: Can our feudal democracy afford to move backward towards Ballot-Box democracy?

By Ritesh Jyoti

Replacing EVMs with ballot boxes seems like a simple fix, but it ignores a brutal history of violence, booth capturing, and caste terror. Can India's feudal democracy afford to go backward?

Communist capitalism is the future of capitalism, not an exception

By Dr. Rahul Sonpimple

The rise of China as a global superpower reveals an unsuspected truth: it’s not capitalists but communists who can run capitalism much better.

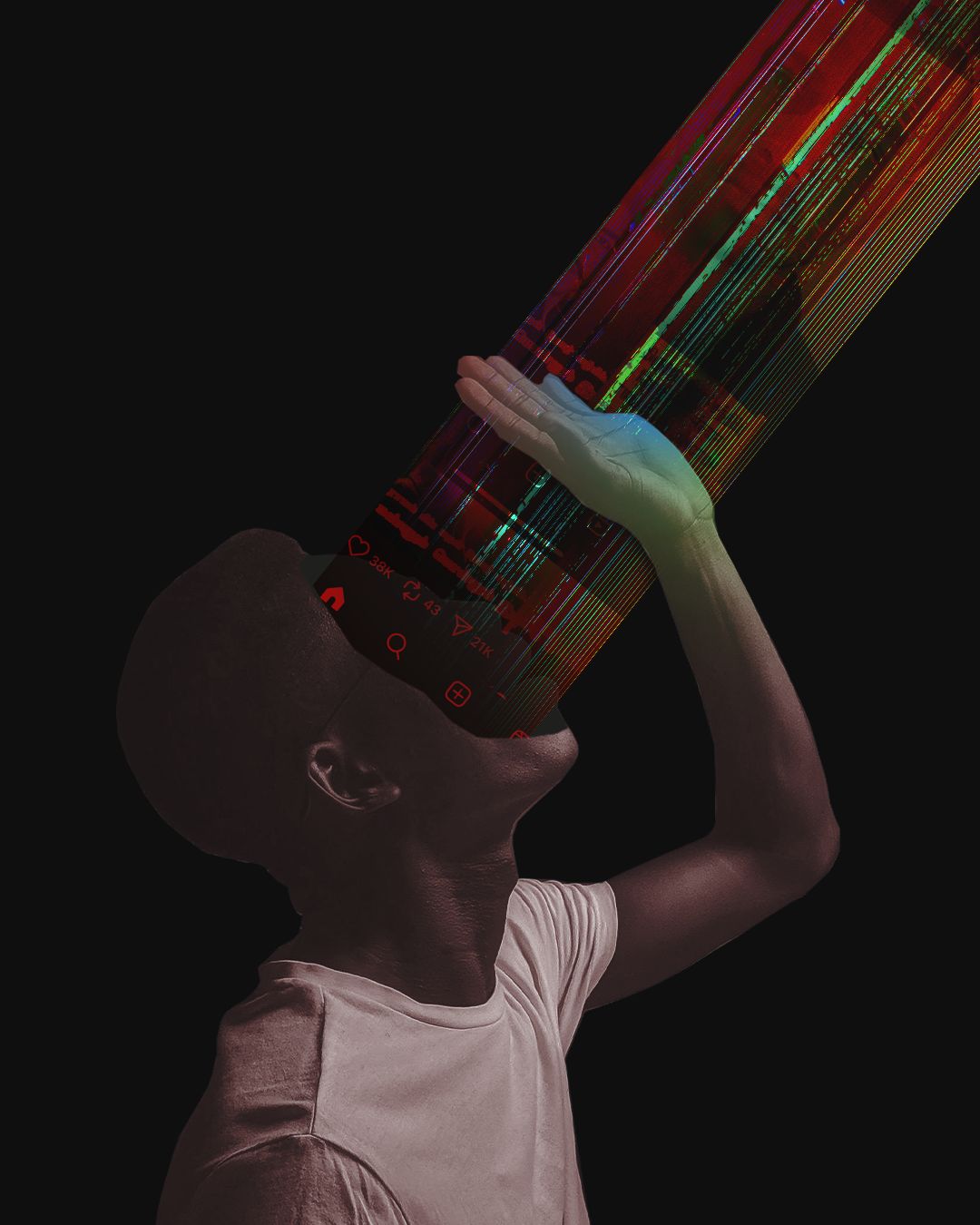

The Algorithm of Caste: Instagram Reels as a 'New' Site of Caste Reproduction and Reinforcement

By Roy Anto

Most of these reels invariably are tied to showcase the dominant caste supremacy, thereby triggering social division based on caste. The local caste politicians, caste party meetings and rallies, village festivals, or sometimes just a group of men enacting hypermasculinity through staged photographs with swords.

Kavin Selvaganesh's murder unearths ugly truths about caste

By Senan R

This murder is not one of its kind, it is an outcome of a deep-seated caste-based inequality materialised in the form of hatredness, sustained and perpetuated in the interest of endogamy/purity of one's caste.

Only a Free Woman Is a Muse.

By Hypatiaa

More importantly WHO was he? WHAT did he represent? Why are Indians so obsessed with his art a century later? Was he really that great an artist? Not really, to my eyes he seems like a hack. And most of the prominent art critics of the time saw him as an imitator of Western Aesthetics. A mimic. So WHY is he so desperately beloved of Indians?

Inherited Pain: How sickle cell reveals the intergenerational violence of caste

By Saumya Barmate

The annihilation of caste is not an ideal. It is the only cure.

20 years of 26 July.

By Shripad Sinnakaar

Now back to that afternoon of 26th July, 2005. I remember waking up to the water cascading in from both sides of the door, since the ledges resisted the stream, the flood hit them from the inside in an upstream, making the flood look like a fountain...

Trapped In Cynicism: The Post-Ideological Liberal’s Opposition and the Everyday of India’s Right Wing

By Dr. Rahul Sonpimple

The liberal does not wish to engage with the forces that produce majoritarian sentiment; rather, they perform their distance from it...

Response to Professor Yogendra Yadav: Ambedkar, Iconization, and The Burden of Radicality

By Sumit Samos

Iconization of Ambedkar Vs Gandhi—Different Histories, Different Stakes

Spontaneity in Ambedkar: Beyond the Passivity of Popular Dalit Discourse.

By Dr. Rahul Sonpimple

Ambedkar did not trust time; he trusted action.

"If God is Dead, Everything is Permitted", Dostoevsky's dictum can have several meanings.

But in Brahminism, everything is permitted under the divinity of gods, from inhumanity to obscenity, everything is sanctified...

Caste in Temple

Merit, Bias, and Belonging: The Silent Battle Against Caste in Universities

Caste on Campus: Part 01

Caste on Campus: Part 02

Archives