In the wake of a massive manhunt in 1983 that saw thousands of police personnel deployed without success, the state failed to capture Phoolan Devi. Following this impasse, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi authorised the Madhya Pradesh Government to negotiate a surrender agreement. Phoolan Devi surrendered at the age of nineteen (19). The terms included assurances that she would not be executed, would be lodged in a Madhya Pradesh jail, and that her family would be rehabilitated - through land allotment and a government job for her brother, among other provisions. After Indira Gandhi’s assassination, successive governments failed to honour one crucial demand: the limitation of her sentence to eight years. Instead, she spent eleven years in prison and was released only at the age of thirty.

In my previous article for The Ambedkarian Chronicle, I wrote about Phoolan Devi’s life after her release about her crucial transformative years she carved out for herself. This piece turns to the period that preceded that public life, her years of isolation in prison and how it prepared her for the new chapter in life.

How did Phoolan Devi spend her years in prison, and what futures did she imagine for herself from behind bars? This article explores these questions through her prison correspondence, contemporary news archives and related documentary material.

Legal appeals

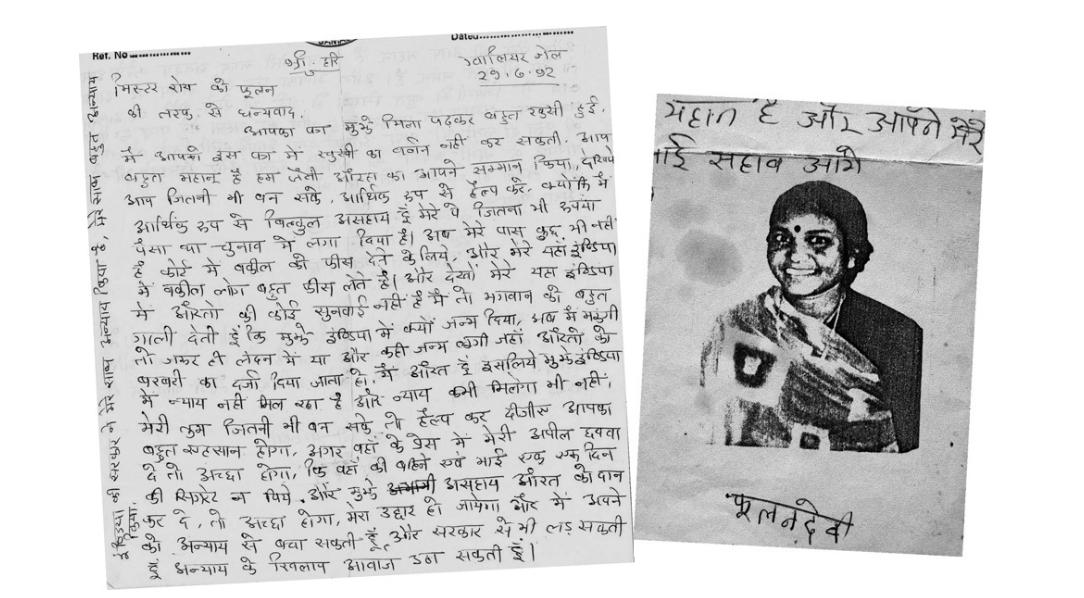

Phoolan Devi, who never had the opportunity to see the face of the school, continued to explore every possible means to secure her freedom from within prison and to assert herself before the world. She submitted multiple appeals to the Apex Court of India, drafting her petitions in Hindi. Disturbingly, the Court refused her a fair hearing on the grounds that they cannot understand ‘Hindi’. ‘Isolated in a single cell, Phoolan Devi has made several appeals through the courts but as she puts it: "Meri bilkul kuch sunahi nahin ho rahi hai. (I am not heard).’ The Times of India, Oct 11, 1992.

Election Debut

In the 10th Lok Sabha elections of 1991, L. K. Advani, then stalwart of the Bharatiya Janata Party, contested from two constituencies one, Gandhinagar and second, New Delhi. He won both the seats and later vacated the New Delhi constituency. The by-election held in 1992 for the vacated New Delhi seat witnessed a closely fought contest involving cinema personalities. Rajesh Khanna contested on a Congress ticket, while Shatrughan Sinha represented the Bharatiya Janata Party. Phoolan Devi contested the election with the support of the Bahujan Samaj Party; however, she was unable to secure the party’s elephant symbol. As history witnesses, Rajesh Khanna won the seat, and Phoolan Devi finished fourth.

This was a time when Devi was fighting a lonely legal battle for herself, even as all her comrades who had surrendered alongside her were released. As noted in the The Times of India archive (October 11, 1992): “During the last 18 months, all the men with whom Phoolan Devi shared her life in the ravines of the Chambal Valley have been freed, in accordance with the ‘deal’—a verbal agreement—struck with Indira Gandhi’ s government.”

By contesting the elections she was building political clout for herself, a strategic move that could strengthen her case for freedom from prison.

Appealing the World from Prison

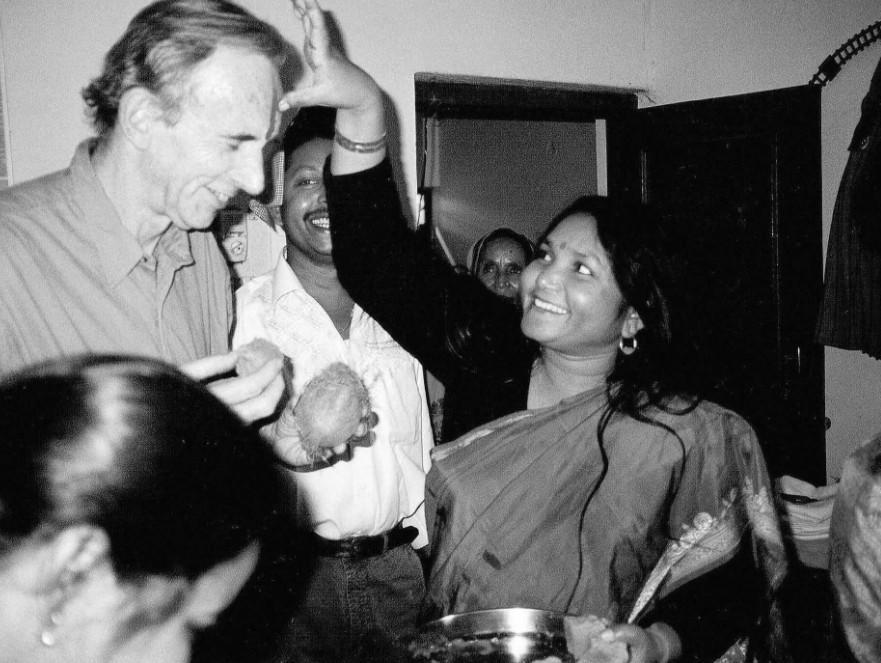

The UK’s The Independent covered Phoolan Devi’s by-election campaign and carried a brief introduction to her life. This coverage marked one of the major turning points in Devi’s story. Among its readers was Roy Moxham, a British national who was then working as a book and paper conservator at the Passmore Edwards Museum in East London. Unsettled by her story, he decided to write a letter to Devi in jail, absolutely unsure whether he would receive any response or at the first place the letter would even reach her.

To his surprise, Moxham received a response from Devi, a letter written in Hindi. Moxham, with great difficulty, eventually managed to translate it into English. Devi saw this correspondence as an opportunity to explore ways that might help her get out of jail. She wrote, “I received your letter at a time when I had lost all hope in life. At such a time, reading your letter gave me the will to live.” She explicitly mentioned her situation to Moxham, stating that all her money had been spent during the by-elections and that she was left with no resources to afford expensive lawyers in India. She requested Moxham to raise a fundraiser for her, asking for nothing more than “just one day’s cigarette money” from sympathetic people in the UK. She also wrote, “I wish I was born in a country like the UK, or anywhere else, where women have equality.”

In response to her appeal, Rox Moxham prepared a resume of Devi and sent it across to his colleagues and friends, he faced disappointment from many doors, yet he managed to gather around Hundred Pounds [around Five thousand rupees then] and sent it to Devi.

“I wish I was born in a country like the UK, or anywhere else, where women have equality.”

Thought of changing the religion

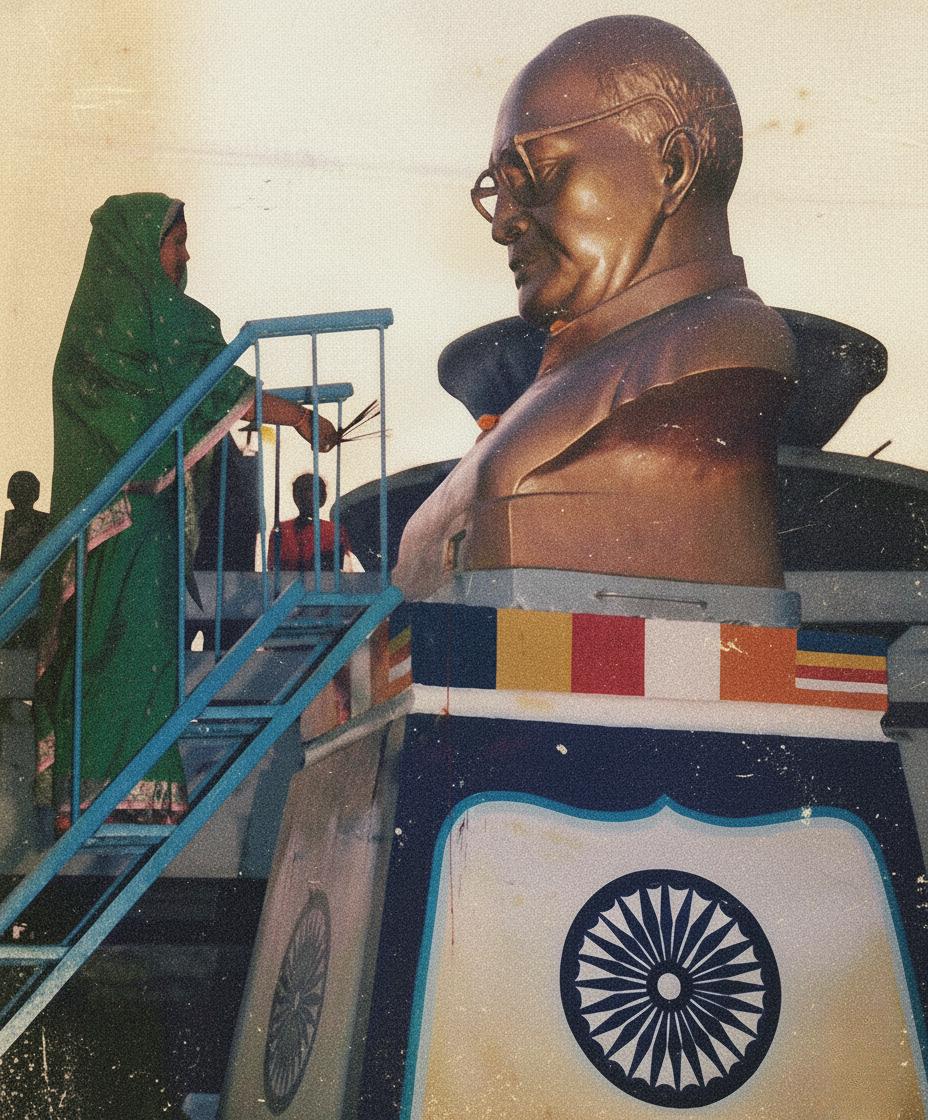

Devi embraced Buddhism on the eve of Ravidas Maharaj Jayanti, on 15 February 1995. However, the thought of changing her religion had taken place much earlier, during her years in prison. Though she never had formal schooling, Devi displayed a keen understanding of society and its structures. She recognised that her own suffering, and that of many women from the so-called lower castes, was rooted in institutional arrangements sanctioned by religion.

Without ever reading him, she clenched the core of what Dr Ambedkar articulated in his 1935 speech What Path to Salvation? that religion exists for men and not the other way around, and that conversion is a necessary step towards reclamation of human personality. From Dr Ambedkar’s call, “To become humane, convert yourselves,” to, “To make your domestic life happy, convert yourselves,” Devi arrived at this understanding through her lived experience.

Devi expressed her desire to change her religion in a prison letter to Moxham dated 16 October 1992. “I am thinking of changing my religion. What religion do you think I should embrace so that I can attain salvation?” she wrote. Interestingly, the letter was written just a day after the anniversary of Dr Ambedkar’s historic mass conversion to Buddhism on 15 October 1956 at Nagpur— a path that Devi herself would follow in 1995 at the same place in Nagpur.

Quest to read and write

After being betrayed and deceived by sarkari babus, her own community, and people she once considered her own, Devi came to realise the importance of knowledge. Her desire to learn how to read and write took place during her hardest days in jail, a period when she often lacked even the will to eat. She made immense efforts to educate herself from within prison, but her continuously deteriorating health eventually made it impossible for her to achieve it. While learning the tactics of the world, understanding the workings of the modern-state and navigating its corrupt institutions, she was in the making of an astute politician.

Deteriorating health

In a letter dated 13 June 1993, Phoolan Devi wrote to Roy Moxham apologising for the delay in her reply, explaining that she had not been keeping well and had been vomiting blood. At first, she believed her condition was caused by the extreme heat of the subtropical climate of Madhya Pradesh, assuming she was suffering from stomach ulcers. After reading her letter, Moxham consulted his brother, who was a doctor, and relayed dietary advice for Devi to follow.

Months later, it was discovered that Devi had developed two tumours in her stomach. In a subsequent letter to Moxham, she wrote: “Brother, I am ill. I have been diagnosed with two stomach tumours—one near the liver and the other near the kidneys. I cannot eat or digest properly and I have a problem with my bowels. I have become very weak. I cannot eat or drink properly or move about, and have to keep lying down all day.”

The court directed that she undergo surgery, and doctors confirmed that an operation was necessary. Devi, however, was reluctant that medical treatment might delay her ongoing legal struggle for release, and she hesitated to consent to the operation. In a following letter, Moxham in strict words advised her that this would not affect her case and urged her to follow the doctors’ advice. Later, in October, Kamani Jaiswal, her advocate, informed Moxham over the telephone that Devi had been transferred to Tihar Jail for treatment at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

Release from the jail

Months later, the following year in 1994, after continuous reporting especially from the foreign media and upon withdrawing of all the cases, around 485 by the Uttar Pradesh Government of SP-BSP government, by Manyavar Kanshiram making the serious case for it, Phoolan Devi was released from the Jail. She writes in her memoir:“A new battle began the day I left the prison, but it was going to be different. I still hardly knew how to read or write, but I knew better how to see, hear, and understand the people and things of this world. I had survived in the villages and jungles, and I prayed to God I would be able to survive in the city, to help those who still suffer the way I suffered.”

Phoolan Devi spent eleven long, lonely years in prison, years that could have crushed anyone. Locked in a single cell, barely able to read or write, she kept fighting. She wrote her case in Hindi to the courts. She ran for Parliament in a by-election while still behind bars. She even wrote desperate letters to a stranger in the UK who became an unlikely ally. One by one, all her bandit comrades from the ravines were freed, but she stayed on, watching the state break every promise made to her. Through failing health, betrayal after betrayal, and sheer isolation, she learned how the system really works: the caste games and the corruption that made her only shrewd.

References:

- I, Phoolan Devi, an autobiography, 1996

- Outlaw by Roy Moxham, 2010

- Times of India Archives