Editor’s note: This article was written before the Supreme Court stayed the UGC Commission Regulations, 2026.

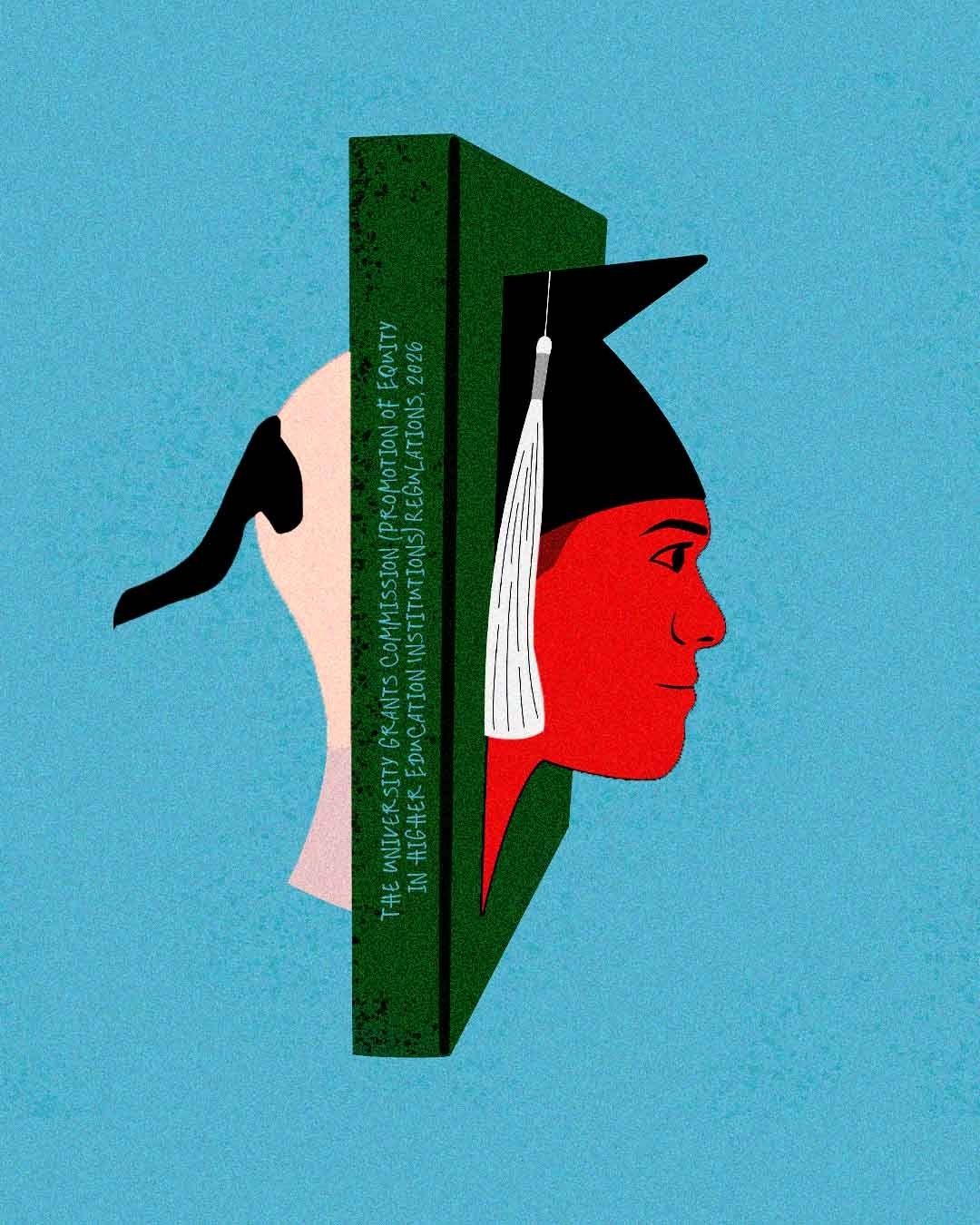

On 13th January 2026, the University Grants Commission (UGC) introduced one of the most significant policy shifts in Indian higher education in years, UGC Promotion of Equity in Higher Education, 2026, to be implemented nationwide. The regulations are introduced to curb discrimination and promote inclusivity on the basis of caste, religion, gender and disability. The regulations replace the earlier Equity Act on Prevention of Caste-Based Discrimination in Higher Education, and places greater accountability on institutions to prevent, identify and address unfair treatment and discrimination based on identity. The enactment of such a bill was much needed, especially given the prevalence of institutional casteism in higher education. To summarize, the UGC Equity Regulations require every higher education institution to establish a Campus Equity Cell, create a multi-level Equity Committee that oversees discrimination complaints, appoint Equity Ambassadors, i.e., trained faculty and students who monitor campus climate, maintain Equity Helplines and online portals for complaint reporting, record, track and time-bound all complaints, offer an appeal mechanism through an Ombudsperson, submit annual equity audit reports to UGC, face penalties, including loss of recognition or funding, if they fail to comply.

In educational institutions, various forms of discrimination towards Dalit, Adivasi, Bahujan, Muslim, queer and disabled students go unchecked. This reform was long overdue. Institutional casteism is not a hidden phenomenon; it is deeply woven into the everyday functioning of universities. Higher education spaces have historically been dominated by upper-caste faculty, administrators, and student networks, and many campuses serve as microcosms of caste society, reflecting its hierarchies in subtle yet powerful ways. Given this reality, one might assume that a regulation intended to protect vulnerable students would be widely welcomed.

However, this is being widely criticised by India’s upper-caste youth who are protesting that such a bill can unfairly frame them as perpetrators and can be misused by the victims. Videos and social media posts frame the regulation as a threat to upper-castes, claiming that it can be weaponised against them. Another absurd argument raised by upper-castes is that the regulations frame them as oppressors when caste discrimination can also happen with them (As reported in this DNA article here: Why general caste students are up in arms against new UGC law?). This raises serious concerns and questions over caste, meritocracy and privilege in contemporary India: (i) How do campuses ensure the smooth enactment of the regulation? (ii) Why is India’s upper-caste youth resisting this Equity regulation? Institutional casteism is systemic, as argued and widely documented by N. Sukumar, in his book titled Caste Discrimination and Exclusion in Indian Universities, Prof. Sukhadeo Thorat’s extensive report Thorat Committee Report: Caste Discrimination in AIIMS, and countless other scholars. Students from marginalised backgrounds consistently report the everyday exclusion, including: isolation in classrooms, being reduced to stereotypes (e.g., quota students), exclusion from informal academic campus life, biased grading or harsher academic evaluation, denial of mentorship or recommendation letters, etc.[1] The regulations have its origins in a petition filed by Radhika Vemula and Abeda Salim Tadvi, mothers of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi respectively, who questioned the implementation of the earlier equity rules. Recently, The Congress-led Karnataka government has proposed to enact the Karnataka Rohith Vemula (Prevention of Exclusion or Injustice) (Right to Education and Dignity) Bill, 2025 to criminalise caste discrimination in Indian educational institutions.

The most common claim of the upper castes is that they will be unfairly labelled as perpetrators. For decades, upper-caste behaviour, whether benign, exclusionary, or discriminatory, has operated without institutional impunity. Now with this new regulation, they are raising an absurd and hollow argument that even they are susceptible to caste-based discrimination. This argument is another manifestation of the idea that reservations disadvantage them or that marginalised students are favoured, and it creates a false equivalence. To suggest that upper-castes face discrimination “equally” is to erase years of history, context and power of Brahmanical hegemony. The “misuse” argument emerges every time marginalised groups gain legal protection from the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, yet data consistently shows that caste-discrimination persists.

“The highest form of violence is when oppressors start behaving like victims.”

The current backlash mirrors one of the most shameful chapters of post-independence India- the anti-Mandal protests of 1990. Back then, upper-caste youth poured onto the streets screaming that “merit” was under threat. They burned effigies, blocked roads, the media amplified upper-caste anxieties as a national crisis and even self-immolated, yet the caste hierarchy remained invisible to them. There are numerous posters circulating on X, calling for mobilisation against the 2026 regulations that feel familiar to anti-Mandal protests. Mandal marked a historic moment when caste privilege in public employment was finally confronted, and the 2026 UGC regulations mark a similar confrontation within higher education spaces. In both moments, upper-caste youth frame structural accountability as persecution, equity as bias, and redistribution as injustice. Their actions remain unchallenged. The intensity of protests today both on-site and online reminds us that whenever the Indian state attempts to democratise access, whether through reservations or equity regulations, it is met with a “savarna resistance”.

One of the few times, there is going to be systemic accountability and punishment for a group that has been engaged in exercising its power in the form of brutal violence against the marginalised communities for centuries. They can’t digest the fact that the power of being inhuman to ‘fellow citizens’ is being taken away from them. Hence, the uproar!

Most universities still treat discrimination on the basis of identity – especially caste-based discrimination – as interpersonal conflict rather than structural harm. Marginalised students often face retaliation, victim blaming, harassment or social isolation for raising complaints. The new regulations attempt to break this cycle. Equity regulations, then, are not just an administrative reform but a structural transformation. This moment is more than a policy shift, it is a test of whether Indian universities are ready to transform themselves. The change is necessary, and the resistance reveals why.

[1] Niraj Athawale, After Rohith: What Changed? The Ambedkarian Chronicle.