There is a reason Dr B. R. Ambedkar remains profoundly dangerous to the present political regime. Not dangerous in the theatrical sense of opposition but dangerous in the way a rigorous intellect unsettles inherited power. Babasaheb does not offer comfort. He does not allow selective reading. Once one enters his analytical universe, it becomes impossible to return unchanged. His writings demand a restructuring of how power, history and democracy are understood in India. This is precisely why certain texts are remembered ritualistically while others are quietly marginalised.

Among the least circulated of his political writings is Maharashtra as a Linguistic Province (1948), particularly the sections dealing with the proposed separation of Mumbai erstwhile Bombay from Maharashtra. The text dismantles with forensic clarity, the alliance between industrial capital, elite journalism and caste privilege that sought to detach Bombay from its linguistic and social geography. Unlike his more frequently cited works on caste, this essay directly exposes how economic power disguises itself as rational federalism and how “national interest” is mobilised to deny democratic self-rule to working-class populations.

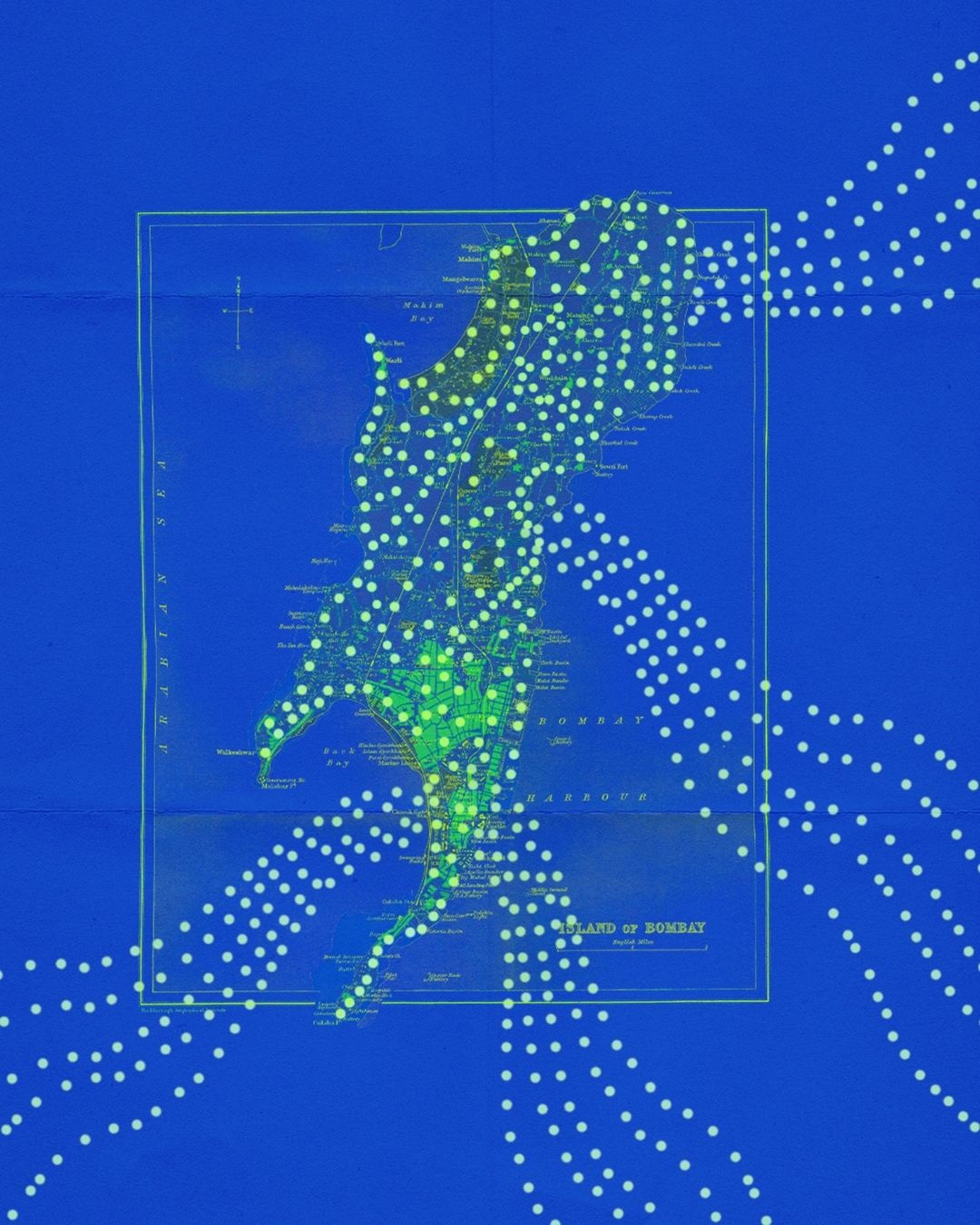

Historically, the question of Bombay was never merely administrative. Babasaheb understood this with absolute clarity when the debate over linguistic states unfolded. For him, language was not a sentimental marker of culture nor a romantic expression of identity. Language was a political instrument that one through which democratic participation, social justice and self-rule could be realised. A linguistic province was not meant to produce homogeneity. It is from this standpoint that Babasaheb examined the “claims” that Bombay should be separated from Maharashtra. Read through this lens, the resolutions passed by a closed meeting of sixty industrialists (1 ChristianChristain and 59 Gujarati Bramhan-Baniya) in 1948 collapse not as flawed arguments alone but as a coordinated attempt to shift political power away from the working classes of the region.

These resolutions were endorsed and amplified through elite English-language journalisms, such as Times of India and mercantile platforms such as the Indian Merchants’ Chamber. Those claimed that Bombay was never part of Maharashtra, never part of the Maratha world, never predominantly Marathi-speaking and that its trade and industry were built exclusively by Gujarati-speaking capitalists. Babasaheb’s first move was methodological. He asked a simple but devastating question: on whom does the ‘Burden of Proof’ lie? If Bombay is geographically, linguistically and materially part of Maharashtra, then the burden of proof rests not with those who claim inclusion but with those who demand separation. This shifting of burden was not rhetorical; it was epistemic. It forced elite opinion to justify itself rather than assume authority.

The first two claims – Bombay was never part of Maharashtra and never part of the Maratha Empire were dismissed by Babasaheb not because they were historically false but because they were politically irrelevant. Indian history which is shaped by conquest without assimilation, could not serve as a basis for democratic reorganisation. Conquest in India layered authority without dissolving social identities. To invoke medieval political boundaries to decide the fate of a modern province was therefore an act of intellectual evasion. The Maratha state’s decision not to annex Bombay militarily, did not render Bombay alien to Maharashtra. It reflected the strategic limits of a land-based power confronting European naval dominance. Babasaheb redirected the debate from romanticised history to material geography. Bombay lay within the unbroken Konkan stretch between Daman and Karwar. Geography, not selective historiography, made Bombay part of Maharashtra. To deny this was to deny fact itself.

The third claim which says that Marathi-speaking people did not constitute a majority in Bombay. This claim was treated by Babasaheb with deliberate indifference. Even if the figures cited by industrialist economists were accepted, he argued, they proved nothing. Under colonial rule, Bombay had been opened to unrestricted migration from across India. Population composition was shaped by imperial labour demands and capital flows, not by any failure of Maharashtrians. To penalise a linguistic community for having been turned into a labour reservoir was to punish the victim for the crime. Demography, Babasaheb insisted, could not override democratic justice.

The fourth and sixth claims was about asserting Gujaratis as old residents and sole builders of Bombay’s trade and industry. Thus it revealed the deeper caste–class logic beneath the resolutions. Babasaheb did not deny Gujarati presence in Bombay. Instead, he interrogated the historical conditions under which Gujarati mercantile power was installed and protected. Archival records from the late seventeenth century show that figures such as Nima Parakh did not arrive in Bombay as equal participants in an open economy. They arrived as negotiators of privilege.

Parakh’s petition to the East India Company demanded more than commercial opportunity. It demanded sacrosanct social insulation: exemption from labour, immunity from arrest, autonomous religious space, protection from physical coercion, preferential treatment in debt recovery and the right to govern internal disputes without external intervention. These demands did not emerge in a vacuum. They drew upon an older political grammar familiar to western India, that was shaping the Peshwai rule where Brahman–Bania sanctity was preserved over the lives and labour of the majority. The insistence on ritual purity, juridical autonomy and exemption from public obligation echoed a precolonial social order in which Brahmanical privilege was maintained through state power.

Gerald Aungier’s role here requires careful reading. He should not be cast as a villain. Aungier governed Bombay at a moment of acute vulnerability. The English position on the western coast was fragile, threatened by Portuguese hostility, regional powers, and internal instability. Aungier himself operated under constant political danger and would later die in suspicious circumstances. His willingness to negotiate with mercantile elites like Parakh was not ideological alignment but administrative survival. At the same time, Aungier was careful to amend these demands, extend protections to other communities and prevent total monopolisation of power. His actions reflect a colonial administrator attempting to stabilise a precarious settlement, not a conspirator engineering domination in isolation.

What matters politically is not Aungier’s intent but the structural outcome. Privileges granted under colonial anxiety hardened into inherited economic advantage. Over time, these protections produced a comprador mercantile class insulated from the risks borne by the city’s working population. To later claim political dominance on the basis of capital accumulated under such conditions was, in Babasaheb’s logic, an inversion of democracy.

“Democracy does not exist to protect property from people.”

The sixth resolution makes this explicit when it reduces Maharashtrians to “clerks and coolies” and elevates industrialists as rightful rulers. This is not economic reasoning; it is caste ideology translated into the language of industry. Babasaheb recognised that behind the resistance to Maharashtra lay a deeper fear: that a linguistic province would empower the working classes including Dalit and Bahujan who formed the backbone of Bombay’s labour force. What the industrialists opposed was not regionalism; it was the redistribution of political power.

The fifth and seventh claims that Bombay belonged to all of India as a trade centre and that Maharashtra merely wanted its surplus. For Babasaheb, it was the most dishonest claim. By this logic, no industrial city could belong to its surrounding region. Every port and factory town would have to be detached from local political control and handed over to managerial elites. Babasaheb rejected this outright. Trade does not cancel geography. Economic importance does not erase linguistic and social realities. Such arguments sought permanent political subordination of producers to owners.

The final claims advocating multilingual states and so-called rational regrouping were equally hollow. In India’s conditions, multilingual states did not protect minorities; they empowered those who already controlled capital, administration and linguistic prestige. A linguistic province, for Babasaheb, it was a defensive democratic structure which one was allowed ordinary people access to governance in a language they lived and worked in. Rationality detached from social reality becomes domination by another name.

What made the resolutions of the sixty industrialists dangerous was not their number but their amplification. Elite journalism transformed class interest into “reasoned opinion”, shifting the burden of proof onto the very people whose labour sustained the city. Babasaheb refused this inversion. That refusal is where this present argument also stands. The burden of proof today lies with those who seek to administratively and culturally recast Bombay as a city of industrial ownership rather than labour, geography and language.

Bombay was built by Dalit, Bahujan and working-class labour, textile workers, dock workers, sanitation workers, construction workers etc. many of whom lived and died without recognition. Capital did not build Bombay; labour sustained it. To convert colonial privilege into political sovereignty is to accept a Brahman–Bania worldview where wealth substitutes for belonging. Babasaheb strip down this logic fundamentally.

This brings me to the most uncomfortable but necessary question: What does Dalit and Ambedkarite politics look like today in Bombay? Chaityabhumi and the 6th December event are sacred. They are sites of mourning, assertion and collective memory. But if Babasaheb is reduced to ritual alone, his radical intellect is neutralised. Babasaheb was not merely a symbol of dignity; he was a relentless critic of political economy, caste capitalism and cultural hegemony. At a time when the state is attempting to administratively convert Bombay into a “Gujarati industrial city”, Ambedkarite politics cannot afford to remain event-centric. We must move from commemoration to intervention. From statues to archives. From slogans to counter-histories.

Babasaheb’s method was clear: expose the structural origins of power, name beneficiaries and refuse sentimental nationalism. Following that method today means interrogating how colonial privileges have been inherited, how industrial capital launders its past, and how linguistic federalism is hollowed out in the name of “development.”

At a moment when history is being administratively rewritten, returning to archives, re-reading colonial arrangements and interrogating inherited privilege is not academic indulgence. It is political necessity. Knowledge here is not neutral. It is resistance. Bombay does not belong to industrialists because they accumulated capital under protection. It belongs to Maharashtra because geography, labour, language and democratic logic converge there. And it belongs to Dalit–Bahujan-Ambedkarite politics because without their labour, there would have been no city to claim.

If Babasaheb taught us anything, it is this: the struggle is not for inclusion within a lie but for shifting the burden of proof and dismantling the lie itself.

References

- Prof. Gheewala—Free Press Journal, September 6, 1948, and Prof. Moraes—Free Press Journal, September 18, 1948.

- Ibid

- Prof. C. N. Vakil, Free Press Journal, September 21, 1948.

- Prof. Gheewala, Free Free Press Journal, September 6, 1948

- Second Governor of Bombay Province and brought radical civic reformed laws those threaten Bramhan-Baniya

- Prof. C. N. Vakil, Bombay Chronicle.

- Prof. C. N. Vakil, at the meeting of India Merchants Chamber.

- Prof. Gheewala, Free Press Journal, September 11, 1948.