From my early childhood, we have listened to various songs about Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar at home, in marriages, and other social occasions. In most of these events, the prominent singers were from the Shinde family, who have ruled this space for a long time. Sometimes, we also heard songs sung by Kadubai Kharat. These voices shaped our Ambedkarite cultural environment and helped us connect emotionally with Babasaheb’s ideology.

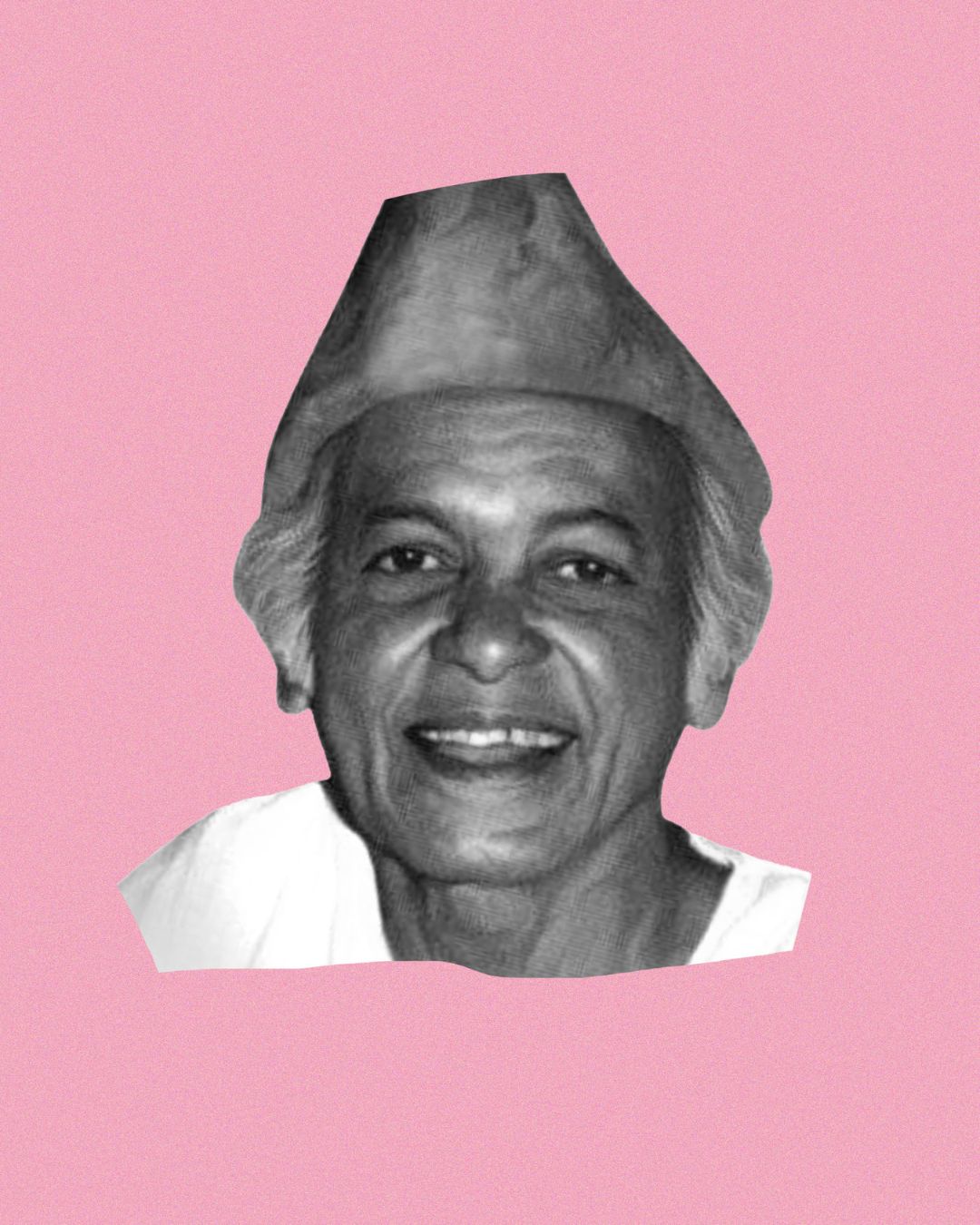

However, among all these singers, one voice feels completely distinct: Wamandada Kardak. His songs were not just performances; they carried thought, pain, and a pointed motive of propagating Ambedkar’s thoughts through music. Even today, the way he used words in simple lyrics continues to mesmerize me. Wamandada Kardak was not merely a singer; he was a cultural force who used folk art to awaken society.

He was born on 15 August 1922 in a small village called Deshwandi in Sinnar taluka of Nashik district. Like most children from poor families, his childhood was spent doing household chores, helping elders, and playing village games. Education was not part of his early life, not because of lack of interest, but because poverty decided his priorities.

At the age of 19, he married Anusayabai. The marriage did not last, and she left him. This personal setback, along with the weak financial condition of his family, forced him to leave his hometown. He migrated to Mumbai in search of work and survival. Like many migrants, he lived in a Bombay chawl, where life was difficult but the fact of its gravity shared by others kept them grounded.

A life-changing incident occurred when a neighbour asked him to read a letter. Until that moment, Wamandada had never fully realized the cost of being uneducated. When he looked at the letter and understood that he could not read even a single line, he broke down and weeped. That moment wounded his self-respect deeply. It was not about one letter, but about lifelong banishment. From that day, he decided to learn reading and writing. With the guidance of Shri Dehalavi, Wamandada slowly began his journey toward literacy.

During the early 1940s, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar was openly challenging the caste system and the discrimination faced by Dalits across India. His speeches and movements were creating political consciousness among the oppressed. Inspired by Babasaheb, Wamandada started attending rallies of the Samata Sainik Dal in Mumbai. In 1943, when he saw Dr. Ambedkar in person, it became a turning point in his life.

From that moment, Wamandada began writing his own songs. He avoided complicated language and elite literary styles. Instead, he chose words that common people could understand and remember. His songs carried anger, hope, dignity, and resistance at the same time. In one of his powerful lines, he directly questions social transformation:

“जग बदलायचं असेल तर, माणूस बदलावा लागतो”

(One has to change oneself in order to change the world)

Through such lines, he made people reflect on their own condition and responsibility. His songs openly rejected humiliation and demanded dignity: “भीक नको आम्हाला, हक्क हवा माणसाचा” (We do not want alms, we want what is ours). For Wamandada, freedom without equality was meaningless, and this thought echoed clearly in his writing: “समतेशिवाय स्वातंत्र्य, अपूर्ण आहे” (Freedom without equality is incomplete).

These were not songs meant only for entertainment. They were tools of education and resistance. Wamandada transformed Babasaheb Ambedkar’s ideology into folk music that could travel from rallies to homes, from streets to hearts.

From a young age, Wamandada wanted to become an actor, but due to social and economic limitations, that dream could not be fulfilled. Instead of surrendering, he found a much larger stage – the streets, public meetings, and social movements. He began putting Ambedkarite thought into folk songs, making it accessible to people who had never read books but could carry songs in their memory for life.

Wamandada Kardak wrote thousands of songs in his lifetime. Some of his important published works include Watanchal (1973), Mohal (1976), and He Geet Wamanache (1977). His songs played a crucial role in spreading Ambedkarite consciousness among the masses. Despite starting life without formal education, he emerged as one of the strongest cultural voices of the Dalit movement.

He received several honors for his contribution to literature and culture and held important positions in cultural and literary bodies. In 1993, he was elected President of the first All India Ambedkarite Literary Conference held in Wardha, a recognition of his lifelong dedication to Ambedkarite thought and Dalit literature.

Wamandada passed away on 15 May 2004 at the age of 81. But his voice did not die with him. His songs continue to inspire generations even today. The man who once cried because he could not read a letter went on to write songs that educated and awakened millions. His life proves that true education is born from struggle, self-respect, and purpose.

It is unfortunate that such a towering cultural figure has not received national-level recognition. Honoring Wamandada Kardak with a Padma Shri would not be an act of charity, but an overdue acknowledgment of his contribution to social transformation. In the Dalit community, the number of poets and singers who created deep ideological impact at the grassroots level is limited, and Wamandada Kardak stands among the greatest of them.

Remembering him is not just about celebrating a singer. It is about respecting a man who turned folk music into political consciousness and pain into power. As long as caste exists, the relevance of Wamandada Kardak and his songs will remain alive.