Although we understand that the newly proposed UGC regulations, have been taken as a calculated move by the ruling BJP to retain power in Uttar Pradesh in the next state assembly elections—especially after the Samajwadi Party-Congress alliance, and specifically the Samajwadi Party, gained power beyond its traditional Yadav-Muslim base through the PDA (Pichhda, Dalit, Alpsankhyak) formula in the last Lok Sabha election—what compels us to go beyond electoral analysis is the Brahmin-Savarna protest against the new UGC rules and the Supreme Court judgment by CJI Suryakant, as well as the response from mainstream media and across political party lines, and even among film celebrities. This points toward the collective consciousness of upper castes and their contempt for equality. Thus, this moment requires deeper analysis.

In Psychoanalysis, more specifically in Lacanianism, a ‘spectacle’ can be rendered to ‘unconscious’ which strives to avoid traumatic experiences of the real. But what if the spectacle, although objectively presenting inverted social reality itself, becomes part of social reality? As Guy Debord argued, spectacle is not just the part of reality but the Spectacle itself constructs the (new) social reality and therefore constructs the ‘Consciousness’. Caste similarly in the modern urban world of Brahmin-Savarna although is part of ‘normal’ i.e., unconscious in its expression, the acceptance or rejection and even in disdain caste scarcely mediated by the immediate subjective experience as many would find in the experiences of Dalits in almost unalienated ways. Moreover, it's rather addressed not by the ‘Everyday’ in sociologically sense but by the ‘Spectacle of Caste’. Such as through the most heinous caste atrocities on Dalits or the extremely poor or helpless condition of Dalits.

Nevertheless, the acceptance of caste through such spectacles protect the Brahmin -Savaranas of what ethically in a Kantian sense can be attributed to ‘Moral Failing’. Such acceptance therefore doesn’t disturb the cognitive order, rather, to put it more clearly it keeps the normal distance from the ‘Other’. What disrupts this routine (re)production of the caste-based cognitive order is a spectacle that emerges as an unexpected rupture, transcending the existing dialectics of ‘otherization.’ For instance, the inversion of established caste stereotypes—such as the humble Harijan versus the privileged Brahmin-Savarna—or disruptions that blur binary distinctions, such as the polite Dalit and the assertive upper caste—challenge the deeply ingrained caste hierarchies. Furthermore, caste beyond this contrast or dialectical visualization assumingly shall rest in silence at least for those whose everyday lives are not minutely or directly automatized by caste like their rural counterparts. However, caste, as mentioned above in the modern Brahmin-Savarna world beyond the routine binary or even beyond the routine spectacles, doesn’t take much of the form of differentiation, mere hatred or even invisibilization. Instead, it leads obscenely to take the form of ‘Contempt’ for lower caste – and mostly against Dalits – the lowest in the hierarchy. Two below recent expressions of spectacles of caste by two known -upper caste -celebrities are quite intriguing to argue why the Second form of Spectacle drives to produce Contempt for Dalits.

Samdish Bhatia - a YouTube journalist known for his satirical style of reporting and conducting interviews with influential Indian personalities in his video titled ‘I Time Travelled To This 18th Century Village in Bihar’ captured acute poverty among Dalits and the everyday presence of untouchability in rural Gaya district of Bihar. While on the one hand this video perfectly fits into the progressive linearity of ‘why caste still matters’ in modern India and why Dalits still deserve to be seen as welfare subjects for the Indian State, on the other it unravels much deeper shared consciousness of urban-metro upper caste that ‘caste exist, but it exists only at a ‘distance’ and therefore the vulgarity of caste shown in the video can only be accepted not as everyday reality of Indian society in general but through a surprisal accident, thus, through the spectacle. Moreover, such acceptance of liberal -politically correct urban upper caste like Samdish Bhatia occurs through the conscious cognitive distance. Yet this very acceptance is good enough to produce the guilt and more so to prohibit the ‘Self Contempt’.

What is important to note here is that guilt ultimately feeds into authentic subjectivity, and the absence of guilt can lead a person to self-contempt which is one of the strongest negative emotions to live. As Nietzsche argued, it compels one to look beyond the existing normativity. The guilt in this context of upper caste liberals in general and more particularly in the context of Samdish Bhatia’s urban upper caste audience is vital for the smooth daily functioning of their socio-psychological cycle. And to satisfy the guilt, you need the authentic subject – the true victim.

Thus, guilt is crucial for the liberal upper caste to consume political correctness yet as mentioned above, it helps them avoid self-contempt. However, while this first spectacle of caste is important to produce guilt for the liberal upper caste, the second spectacle of caste comes as a threat to the protected image of the ‘Savarna Self’. In May 2018 filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri known for his controversial film The Kashmir Files on a flight saw a great Dalit leader’s grandson sitting on 1A (business class), and wrote on his twitter handle:

“Flying, sitting behind a Lower caste leader. But who is the upper caste in today’s scenario? The one sits in business class 1A being attended by ground staff or the ones who are trying to find half inch space for their elbows on the armrest. I was born a Brahmin and this leader was born a Dalit. But today as he sits on 1A and me on 26B the pyramid is inverted”.

To this, while many responded on social media accusing Agnihotri of invisibilizing caste oppression in modern India, including acclaimed filmmaker Neeraj Ghaywan (who publicly declared his Dalit identity) and rose to fame with his 2015 film Masaan, Agnihotri’s tweet, in a deeper sense, was more than anything about caste. It was not just a sally of wit, or a vague attempt to draw a comparison between caste and class, but this can be understood how the normal of caste i.e., unconsciousness of caste confronts the unexpected spectacle surpassing the normal boundaries of expressions.

The regular social and mental negotiation of upper castes with caste is balanced by canned imaginaries of Dalits, such as being poor, humble, helpless, or even overly assertive in the case of liberal upper castes. For the upper caste, the existence of Dalits, therefore, remains positioned on an axis—either showcasing vulnerabilities or performing heroic, assertive acts—routinely devoid of the normal. Thus, Dalit being rich or Dalit being ‘evil’ come as a spectacle which breaks the cognitive negotiation of upper caste and in Lacanaian sense it poses a threat to the Savarana Self i.e., ‘I’.

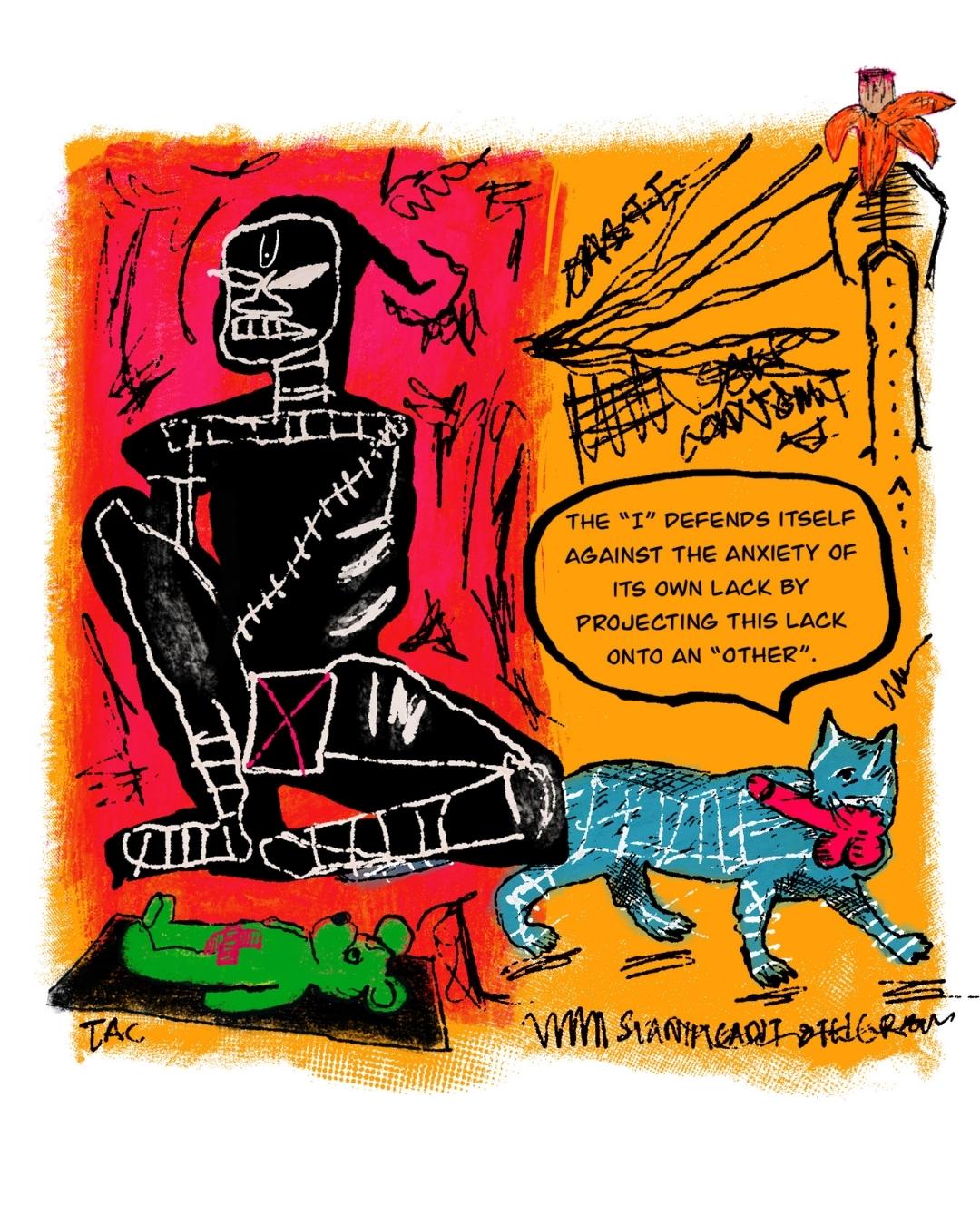

As Lacan argued in his mirror stage, “the "I" defends itself against the anxiety of its own lack by projecting this lack onto an "Other"”, and very expression of this projection occur through the Contempt for the Other who surprisingly stops completing the lack to which ‘I’ is habitual. In the case of Vivek Agnihotri, the Dalit sitting in business class was not the Savarna's idea of a Dalit. Therefore, if one closely examines his tweet, it was less about the changing social or economic situation and more about the portrayal of the 'deviant Dalit'—the contemptuous being. Thus, while Agnihotri's tweet and later his defense appeared to many as an attempt to invisibilize caste oppression or Dalit suffering, I argue that it was more about a deeper expression of the imbalance within the 'I'—his Brahmin self.

Agnihotri’s portrayal of a Dalit sitting in business class also highlights what could be considered absurd in the Brahmin-Savarna world. As Kant simplifies, “contemptible can be portrayed in the language of praise to make the absurdity more apparent.” Clearly, this portrayal of the ‘rich Dalit vs. poor Brahmin’ is not unique to Agnihotri's case; it represents a mythical binary embedded in the well-constructed shared consciousness of post-colonial India's upper-caste mindset. Through many such binaries, the shared consciousness of contempt for Dalits is well-protected in the Brahmin-Savarna world. We will explore this phenomenon in the following section.

The Contempt for the Significant Other and the Consciousness of Caste

In feminist understanding, the control over power positions in public is an inevitable outcome of the distinctions and hierarchy existing between men and women in the personal sphere. Pateman (1983), therefore argued that,

“the dichotomy between the private and the public is central to almost two centuries of feminist writing and political struggle; it is, ultimately, what the feminist movement is about” (p.281).

However, in the context of caste the Public-Private Dichotomy does not operate in the absolute differentiation of power merely between men and women. While caste legitimizes the power in public for both men and women of upper caste, it reduces both Dalit men and women as powerless.

The common and traditional presence of caste that we witness is mostly through the public imageries that include “Dalits are not allowed to drink from the same wells, attend the same temples, wear shoes in the presence of an upper caste, or drink from the same cups in tea stalls” and prohibitions such as Dalits are punished to have honourable and profitable employment, the residential segregation requiring Dalits to live outside the village, the restrictions on lifestyle that Dalits shall not be seen in public to enjoying luxury or comfort same like upper castes, denial of services provided by barber, washer-men, restaurants, shops, theatres etc, and imperatives of deference in the forms of address, language, and sitting and standing in the presence of higher castes and so on.

Moreover, the reproduction of caste as Ambedkar (1917) argued that while guarded by the continuation of endogamy, the hierarchical or the graded inequality embedded in caste survives mostly by the public performance of each caste within the prescribed social and cultural boundaries. In this regard Ambedkar argued that (1979: 56):

“A Hindu’s public is his caste. His responsibility is only to his caste. His loyalty is restricted only to his caste. Virtue has become caste-ridden and morality has become caste-bound.”

However, for our immediate reasoning, these common imaginaries of caste can be linked to the traditional caste-village society and can also be viewed through the lens of ‘hate’ towards Dalits. For these reasons, Brahmin-Savarna 'caste' may appear as a distant reality, almost a non-existent phenomenon in their everyday urban interactions. However, no contemporary scholar of caste would make the mistake of denying the existence of caste simply by observing the absence of overt violence against Dalits or the lack of minute regulation of caste norms in modern urban public life. So how does then caste find its expression in the modern urban Brahmin-Savarna world? Well if caste does not find its expressions necessarily through the hate then it takes an active form of contempt. And here, contempt, unlike hate, does not kernel in the recognition of the other (as hate inherently requires the acknowledgement of the object, person, or situation it opposes). Rather, contempt is articulated through the deliberate act of rendering the 'Significant Other'—such as Dalits—invisible, thereby erasing their presence and significance. Schopenhauer’s reflections on human nature in this context may lend us precise distinctions between hatred and contempt:

“True, genuine contempt, which is the obverse of true, genuine pride, stays hidden away in secret and lets no one suspect its existence: for if you let a the person you despise notice the fact, you thereby reveal a certain respect for him, in as much as you want him to know how low you rate him — which betrays not contempt but hatred, which excludes contempt and only affects it. Genuine contempt, on the other hand, is the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another.”

Contempt, therefore, enigmatically manifests through the paradoxical act of acknowledging the prohibition against recognizing the prohibited as a Significant Other. In a deeper sense, the cycle of contempt can only be said to reach its completion through either silent acquiescence or explicit acknowledgement by the Other. This suggests that, while contempt is imbued with an awareness of prohibitions, the latent desire for recognition by the Other remains inscribed within its reflexive unconscious. A clear example of this can be found in caste-based matrimonial ads published by Brahmin-Savarnas in newspapers and on digital platforms, often stating: Caste no barrier except SC/ST. One may understand this as merely an act of hatred but as mentioned earlier hatred demands to recognise the other. Here, retrospectively, the Brahmin-Savarna applicant first acknowledges the boundaries of prohibitions—that is, they first recognize their own caste boundary—and later desires recognition of this prohibition from the prohibited, and thus from the significant other, namely Dalits and Tribes. This in essence enables the Brahmin-Savarana- the dominant subject to restore the self the imagery as a superior self in the social–symbolic order within which the (Dominant) subject forms his/her identity in relation to the other i.e. immediate social group’s norms (here caste norms). And as the function of caste is more about the minute guidelines of ‘what one shall not do’ than ‘what one should do’, here, the prohibitions of caste in the Lacanian sense play a role of ‘first other’ for Brahimin -Savarna. Nonetheless, in this case, as explained above, the recognition by the Dalit i.e. Out Caste, performs as ‘Significant Other’ which plays an important role in maintaining the illusory wholeness of the reflected image of superior self. And the crucial point not to be missed here is that within this dialectic of recognition by the first other and desire to be recognised by the significant other, the subject's failure (here Brahmin-Savarana) to obtain desirable recognition by the significant other (here Dalits) takes an ugly form of contempt for the significant other. In the context of caste and contempt therefore, when Dalit denies the authority of Brahmin-Savarana or surpasses the existing dialectical boundaries of caste-bound relationship, particularly in modern -urban settings, the Brahmin-Savarana produces the uglier form of contempt. Most importantly, contempt here works as an ‘Inverse Fetish’ wherein the dominant subject ( Brahmin-Savarna) after the misrecognition by the Significant other ( Dalit) actively denies the lack i.e. the desire to be recognised. And to authenticate this very denial or what Zizek has encapsulated an ‘ideological disavowal’, of the dominant subject involves invisiblising the significant other.

Further, this invisilibisation itself becomes part of normal – inseparable from the everyday ideology of the Dominant subject that there requires no conscious or extra efforts for dominant subject ( Brahmin-Savarana) not just to invisibles the significant other ( Dalits) but more conspicuously in Schopenhauer words it leads to “devaluation into nothingness; it marks a judgment of a person being beyond consideration and unworthy of respect, even such respect as to be despised”. For instance, what should be the moral response of a civilized society—an institution or an individual—to the pattern of suicide cases among individuals belonging to a particular ethnic or marginalized social group? If not for long, then at least to avert the immediate moral failing, one would supposedly consider the causes, often spoken of in the context of suicide, worthy enough to introspect. However, the suicides of Dalits and students belonging to lower castes in India’s premier educational institutions and universities—mostly headed and populated by Brahmin-Savarna faculties—find the most common response from upper-caste faculties and students as one against the reasoning of caste discrimination. Instead, these deaths are attributed to poor academic performance, i.e., a supposed lack of merit to cope with academic pressure.

In 2021, Dharmendra Pradhan, the Union Minister of Education, presented a written response in the Lok Sabha stating that 122 students had committed suicide in IITs, NITs, Central Universities, and IISERs in the period between 2014 and 2021, with most of them belonging to Dalit, Adivasi, and other backward communities. While speaking to my IIT PhD scholar friend in Mumbai after the suicide of Dalit student Darshan Solanki in 2023, I wondered as he reported that the day Darshan committed suicide, everything was running as usual, and even the next day and the days that followed, everything remained normal for the department Darshan was studying in, and for the faculty and administration. Apart from the students and faculty belonging to marginalized caste backgrounds, life for the Brahmin upper castes carried on as if nothing had happened.

“Contempt, unlike hatred, numbs one to the most horrific acts against humanity, rendering them invisible. It allows for the complete erasure of the other.”

This indifference becomes apparent through IIT Bombay's usual response, similar to that of other upper-caste-headed educational institutions, where although an internal probe panel linked the recent suicide of a Dalit student on campus to academic performance, at least three surveys conducted by the SC-ST Student Cell pointed to a highly discriminatory atmosphere on campus towards students from Dalit and Adivasi communities. Can one maintain such normalization even after a suicide occurs in their vicinity without harbouring contempt? In the context of higher education in so-called premier institutions, the entry of Dalit students and faculty disrupts the traditional social and cognitive distance of caste for Brahmin-Savarnas. As previously mentioned, the misrecognition of the Savarna self ultimately manifests in acts of invisibilization, reducing Dalits and other marginalized castes to nothingness. Eichmann—the Nazi officer who coordinated the deportation of Jews to extermination camps and played a crucial role in arranging the logistics of the Holocaust—was described by Hannah Arendt in her Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963) as an ordinary man, not a fanatic, merely following orders from above. Arendt’s portrayal of Eichmann as an unremarkable bureaucrat underscores the normalization of horror. This normalization cannot simply be attributed to hatred. As I argue, such normalization is deeply tied to contempt, which reduces the other to a state of nothingness without requiring active or conscious effort to harm.

Contempt, unlike hatred, numbs one to the most horrific acts against humanity, rendering them invisible. It allows for the complete erasure of the other, a process that requires neither passion nor engagement but instead an automated indifference. This indifference, rooted in contempt, enables the perpetuation of extreme obscenities without the recognition or acknowledgment of the moral weight of the acts performed. Further, this atomization or unconscious of Contempt - here in the case of Brahimin -Savarana - cannot be simply an internal belief to be carried out in the personal sphere, though a priori in a psychological sense its shape and its direction and authorization deeply originates in the extremality of symbolic system and shared belief and therefore into the collective consciousness of Brahmin-Savarana. And which is the reason though ‘contempt for other’ would fall as a negative emotion in moral reasoning, its cognitive as well moral sanction within the Brahmin-Savarna world is not simply inscribed into the individual experience but embedded into the collective expression which in Durkheimian sense sustains the social solidarity and bound the Brahmin-Savarana individuals together in a community. Thus, Contempt is an emotion within this terrain of intimate belief and external -socio-symbolic machine that is produced and experienced as an objective social fact by the Brahmin-Savarna.

References

- Slavoj Žižek, How to Read Lacan (London: Granta Books, 2006), 3: "For Lacan, psychoanalysis at its most fundamental is not a theory and technique of treating psychic disturbances, but a theory and practice that confronts individuals with the most radical dimension of human existence."

- “It is not an image that stands for the Real, but an imaginary framework that conceals the real mechanisms of power and social relationships.” — Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), p. 106.

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (Detroit: Black & Red, 1983), 12

- Immanuel Kant, Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (Yale University Press, 2002), 4: "Moral failing occurs when an individual fails to act in accordance with the moral law, particularly in terms of duty and universal principles."

- "I Time Travelled To This 18th Century Village in Bihar | Bharat Ek Khoj Ep18 | Unfiltered by Samdish," UNFILTERED by Samdish, YouTube video, 28:35, published on April 14, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0w2u5qRz2k.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals (Trans. Walter Kaufmann, New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 19: "Self-contempt, one of the strongest negative emotions, compels one to transcend the established norms and look beyond the conventional morality."

- "The 'I' is the mental representation of the subject's own image, formed in the mirror stage, where the subject sees itself as a whole for the first time. But this recognition is also a misrecognition, as it involves the projection of the subject’s internal lack onto an external Other. This projection gives rise to anxiety and contempt, especially when the Other no longer fulfills the role of completing the lack that the 'I' has constructed." — Jacques Lacan, Ecrits: A Selection (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1977), 2.

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1987), 88

- Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983), 281.

- Hillary Mayell, "India's 'Untouchables' Face Violence, Discrimination," National Geographic News, June 3, 2003, https://news.nationalgeographic.com.

- Namala, "Discrimination and Violence Against Women in Ghana", United Nations, 2009, https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/egms/docs/2009/Ghana/Namala.pdf.

- B.R. Ambedkar, The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables? (Delhi: Buddha Mahila Prakashan, 1979), 56.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 2.

- Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 26: "The ideological disavowal is the process by which a subject acknowledges a truth but simultaneously denies it, thus maintaining the illusion of a different reality while still acting according to the ideological framework."

- Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Basis of Morality (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), 87.

- Sukanya Shantha, "IIT Bombay Suicide: Did Authorities Fail to Act Even After Surveys Pointed to Rampant Casteism?" The Wire, March 2023, https://thewire.in.

- Emile Durkheim, The Division of Labour in Society (New York: Free Press, 1997), 150.