1

“Don’t these guys get bored with making films again and again and again on the feuds between the upper caste and the oppressed caste people? A brilliantly shot and brilliantly performed, BORING film.”

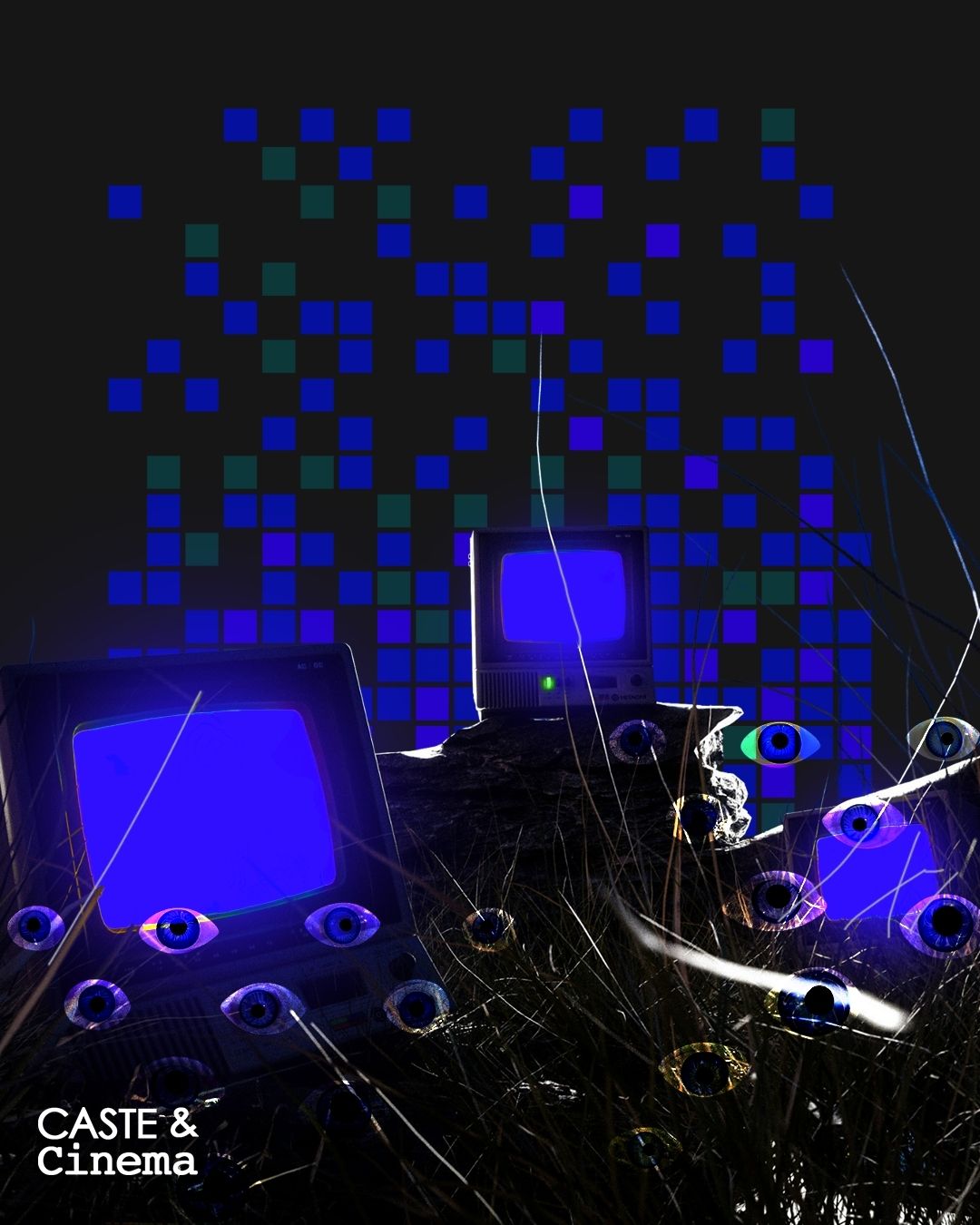

"Anti-caste cinema refuses the distance between the viewer and the cinema; it does not offer the Savarna gaze the comfort of detachment. The Savarna gaze cannot hold that mirror for too long."

2

“With the establishment of a relationship of oppression, violence has already begun. Never in history has violence been initiated by the oppressed. How could they be the initiators, if they themselves are the result of violence? How could they be the sponsors of something whose objective inauguration called forth their existence as oppressed? There would be no oppressed had there been no prior situation of violence to establish their subjugation.

Violence is initiated by those who oppress, who exploit, who fail to recognise others as persons – not by those who are oppressed, exploited and unrecognised….

Whereas the violence of the oppressors prevents the oppressed from being fully human, the response of the latter to this violence is grounded in the desire to pursue the right to be human… As the oppressed, fighting to be human, take away the oppressors' power to dominate and suppress, they restore to the oppressors the humanity they had lost in the exercise of oppression.”