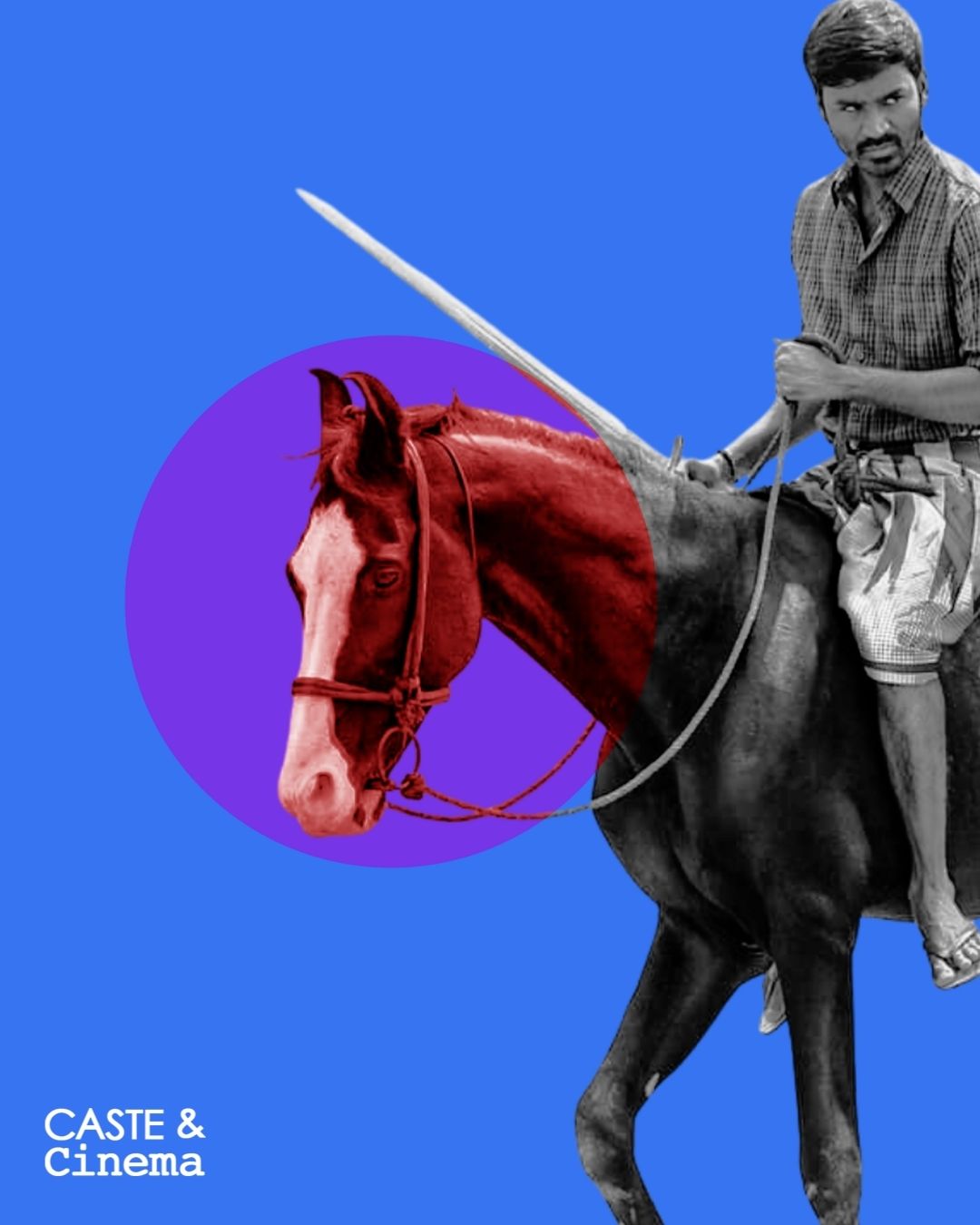

Who gets to care for an animal?

What should this care look like?

Who gets to rescue animals?

Which animals are getting rescued from whom?

“You may touch your horse, you may pat your dog, you may stroke your cat, but you may not touch an Adi Dravida or Adi Andhra.”

“You may breed cows and dogs in your houses, you may drink the urine of cows and swallow cow dung to expiate your sins but you shall not even approach an Adi Dravida.”

Kinship

Breaking the bigoted binary

Film language of fraternity

Subverting the saviour complex

“My father who never even knew how to swim,

Was the one who taught me to surf the waves.

My father, who never even looked up at the sky,

Was the one who taught me how to fly.

Gathering molten splashes of wild fire that day,

My father rolled it and gave it to me,

And that’s the cool sun, always with me”.

References:

- Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches

- ‘Beings and Beasts, Human-Animal Relations at the Margins’ edited by Ambika Aiyadurai and Prashant Ingole

- ‘The Pig, the National Anthem and Anti-caste Belonging in Fandry’ by Purnachandra Naik

- ‘Speaking of Pain: Portrayal of Human-Animal Relations in Tamil Cinema’ by R.Samuel Gnanaraj

- ‘Cast(e)ing Animals in Cinema: Exploring Human-Animal Relations through Fandry and Pariyerum Perumal’ by Akshay Sawant

- ‘Indifference, On The Praxis of Interspecies Being’ by Naisargi N.Dave

- Status of Cow Shelters by Government of India, Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying

- Violence in the name of cows: The ‘animal welfare’ groups that beat up truck drivers in India by Pooja Chaudhuri, Shinjinee Majumder & Abhishek Kumar for Alt News

- ‘ “Cow Is a Mother, Mothers Can Do Anything for Their Children!”Gaushalas as Landscapes of Anthropatriarchy and Hindu Patriarchy’ by Yamini Narayanan

- ‘Brahmin, anti-caste, caring for cows — a writer walks on eggshells of Hindutva & Ambedkar’ by Antara Baruah for The Print

- ‘What’s Unholy About The ‘Holy Cow’ Discourse?: Reclaiming ‘Animal Welfare’ From The Far Right’ by Rohin Sarkar for Feminism in India

- ‘Love in the Time of Caste: Dalits and Animals in ‘Vaazhai’ and ‘Pariyerum Perumal’ ‘ by Sowjanya Tamalapakula for CounterCurrents.Org

- ‘Animating caste: visceral geographies of pigs, caste, and violent nationalisms in Chennai city’ by Yamini Narayanan

- The Oppressed Hindus by M.C. Rajah

- மகிழ்ச்சியான பன்றிக்குட்டி by வெய்யில்

- India’s invisibilisation of donkey labour is rooted in the caste system by Anchal Kumari, Vinayak for Down To Earth