Jai Bhim!

Namo Buddhay!

This is not only a story of what Dr. Ambedkar wrote to then popular English economist and a Marxist expert on Soviet economy, Mr. Maurice Dobb, as the title may suggest. But it is also a story of a book particularly identified by Dr. Ambedkar to be of great help for his personal and educational usage.

Mid-1940s was a period of uncertainty in Indian politics. More so for Dr. Ambedkar and his people. India’s independence was on the cards and yet there was no certainty as to the fate of the one-sixth of its population (the Untouchables or Depressed Classes) under the incoming travesty of the ruling castes under the garb of the so-called “Independence”. Dr. Ambedkar in a long letter, dated 14th May 1946 (BAWS, Vol 17_2), to Mr. A. V. Alexander, member of the Cabinet Mission (1946), listed various reasons for why this Mission was sure to put the case of the Untouchables in a dire situation unless constitutional safeguards were put forth and separate electorates granted. When a “..machinery whereby Indians can frame their own Constitution for an independent India..” (Lord Pethick Lawrence’s letter dated 28th May 1946) was being brought into force, voices from UK’s own Parliament erupted in favour of having Dr. Ambedkar being involved in the process. In a speech of July 7 1946, Sir Samuel Hoare (then Secretary of State for India) made the case for bringing in Dr. Ambedkar into the discussions of making the constitution by informing the Parliament that Dr. Ambedkar "is one of the ablest public men in India". He went on to explain how the Poona Pact, brought about by Gandhi's fast, “left [Dr. Ambedkar] with practically no representation.” He was then joined by The Earl of Scarborough who said, “I would expect, that the Congress Party would recognise how important it is that, that great and important minority of the Scheduled Castes should have the satisfaction of feeling that their case to the Constituent Assembly will be presented by those who have their greatest confidence”. It was notable when Sir Stafford Cripps joined in the debate to express their Government’s inability to get Dr. Ambedkar elected into the Constituent Assembly due to the Poona Pact which worked against him. It was in these circumstances that Dr. Ambedkar sought (in July 1946) a copy of a petition that the famed American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois’s group had made at the U.N.O. Soon after it became clear that it was necessary that a case had to be made in person, Dr. Ambedkar flew from Bombay to Karachi airport on Oct 14th, on his way to London. After sending letters to Clement Attlee (with whom a meet was also set in this trip), Samuel Hoare, Churchill and others, Dr. Ambedkar even stayed at Churchill’s country home in Kent. His short visit to London during this time deserves a different space altogether.

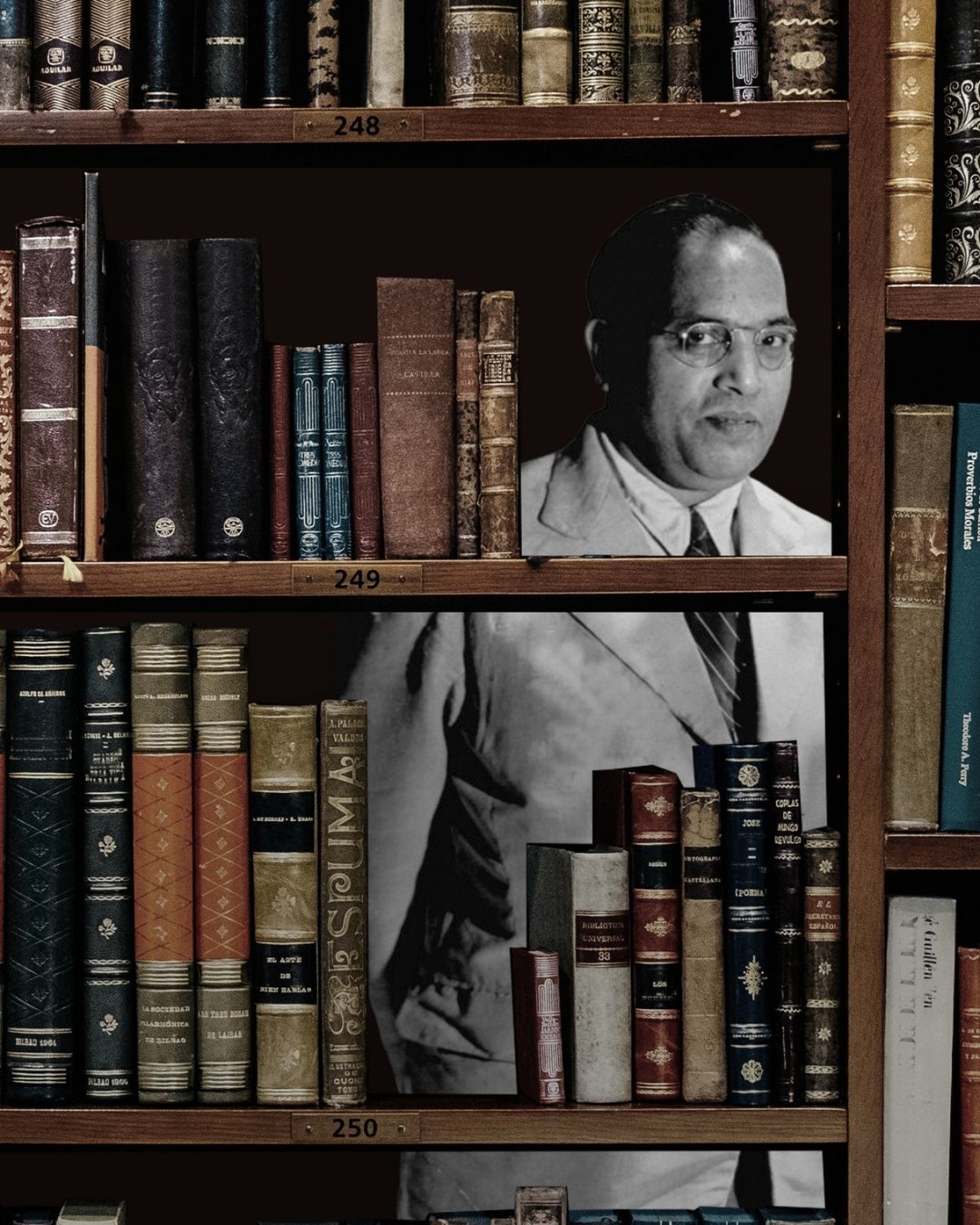

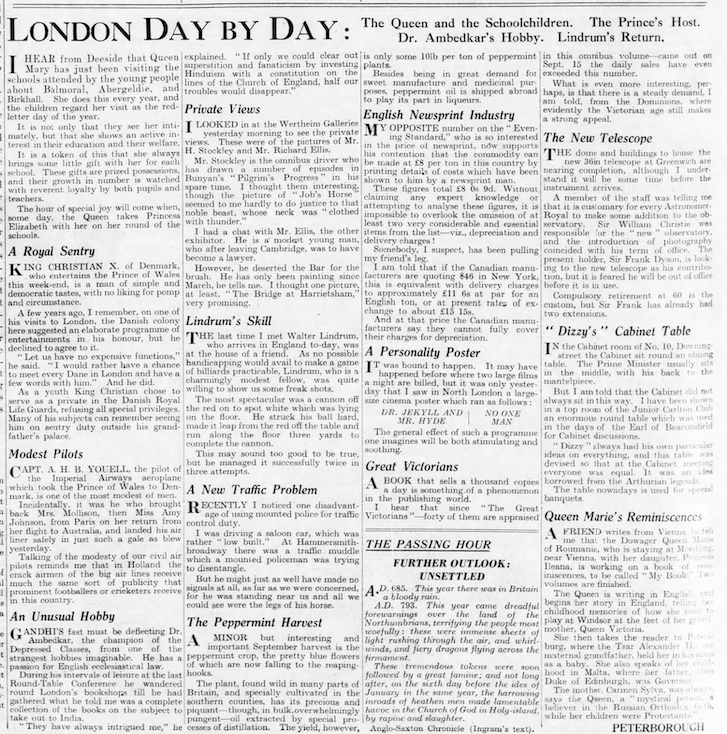

It is not a fanciful thought but a well-documented fact that whenever Dr. Ambedkar found himself in London, he would go shopping for books on various topics. This would be apparent to anyone who had read his letters throughout. An independent recounting of this can be found on The Daily Telegraph’s popular “The Peterborough” weekly column (which was revived recently), from 23rd September 1932 (a day before the Poona Pact was signed):

London Day By Day: The Queen and the Schoolschildren. The Prince’s Host. Dr. Ambedkar’s Hobby. Lindrum’s Return.

An Unusual Hobby

Gandhi’s fast must be deflecting Dr. Ambedkar, the champion of the Depressed Classes, from one of the strangest hobbies imaginable. He has a passion for English ecclesiastical law.

During his intervals of leisure at the last Round Table Conference he wandered round London’s bookshops till he had gathered what he told me was a complete collection of the books on the subject to take out to India.

“They have always intrigued me,” he explained. “If only we could clear out superstition and fanaticism by investing Hinduism with a constitution on the lines of the Church of England, half our troubles would disappear.

It must have been on one of those wandering abouts, a decade later, not completely undeflected by the current crisis, that Dr. Ambedkar was looking for something very specific: books on Soviet economics by Maurice Dobb – a contemporaneous student from LSE!

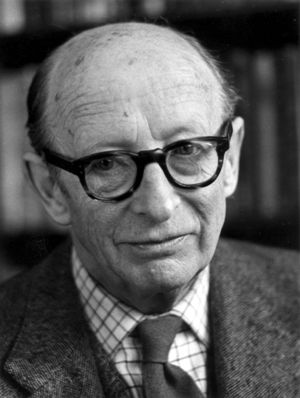

To present a short sketch, Maurice Dobb was a Cambridge-based Marxist economist who did most of his work on Soviet Economics and had cultivated a very niche and respected name in that field. Born in 1900 in London to a landowning prosperous family, he underwent education at a well-established public school (Charter House School) in the countryside that was founded in 1611. Initially enrolled into Pembroke College, he soon moved into London School of Economics around the same time (1922-24) that Dr. Ambedkar did, and the same teacher - Edwin Cannan! It was around this time that he also joined the Communist Party of Britain recruiting members for it. After his PhD from LSE, he moved to Cambridge in 1924. He could be accredited to have been “perhaps the single person most responsible for bringing Marxian economics into the modern day.” In a 1989 interview published on Journal of Economic Perspectives, of Dr. Amartya Sen (Nobel Prize in Economics, 1998) who was, interestingly, a student of Maurice Dobb, had described him in these words:

Arjo Klamer: “With whom did you study in Cambridge?”

Dr. Amartya Sen: “I had Maurice Dobb and Piero Sraffa as my teachers at Trinity College.”

Arjo Klamer: “Were they important for you?”

Dr. Amartya Sen: “Yes, Maurice Dobb particularly because I was interested, as I already said, in politics besides economics. He was a very well-integrated scholar in political economy. He was a Marxist, but most widely read in other traditions as well. He was one of the least dogmatic persons one can think of. He made me very interested in such classical problems as the motivation behind the theories of value.”

You could see this acknowledgement extended onto the biography of Dr. Amartya Sen on the Nobel Prize’s official record: “Maurice Dobb, who was an astute Marxist economist, was often thought by Keynesians and neo-Keynesians to be “quite soft” on “neo-classical” economics. He was one of the few who, to my delight, took welfare economics seriously (and indeed taught a regular course on it)...”

Associated as he was with the Marxist groups in Britain, he was also a teacher and a friend to Eric Hobsbawm, one of the greatest Marxist historians of the West. If that wasn’t enough, Dobb was also John Maynard Keynes’ “favourite student”!

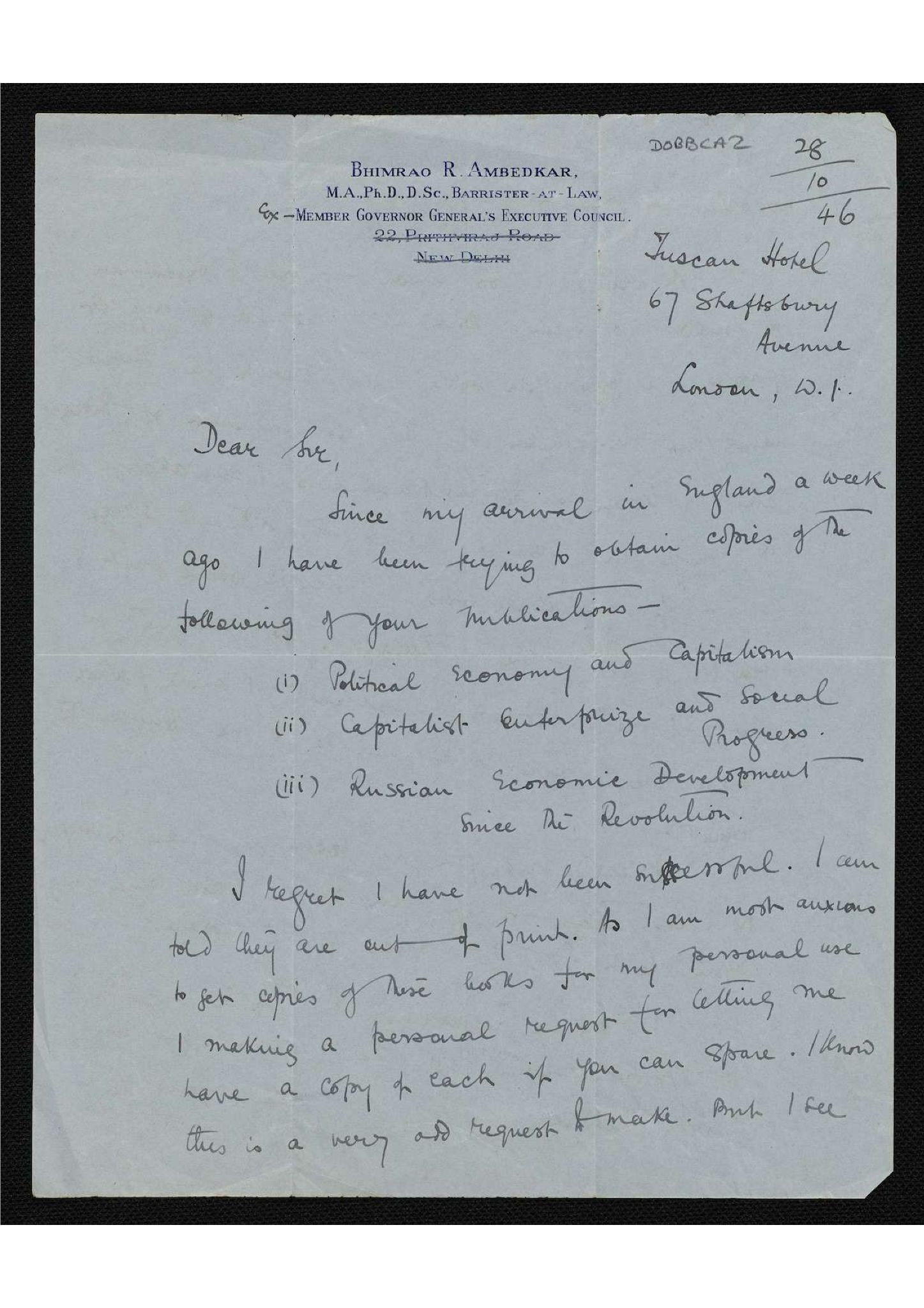

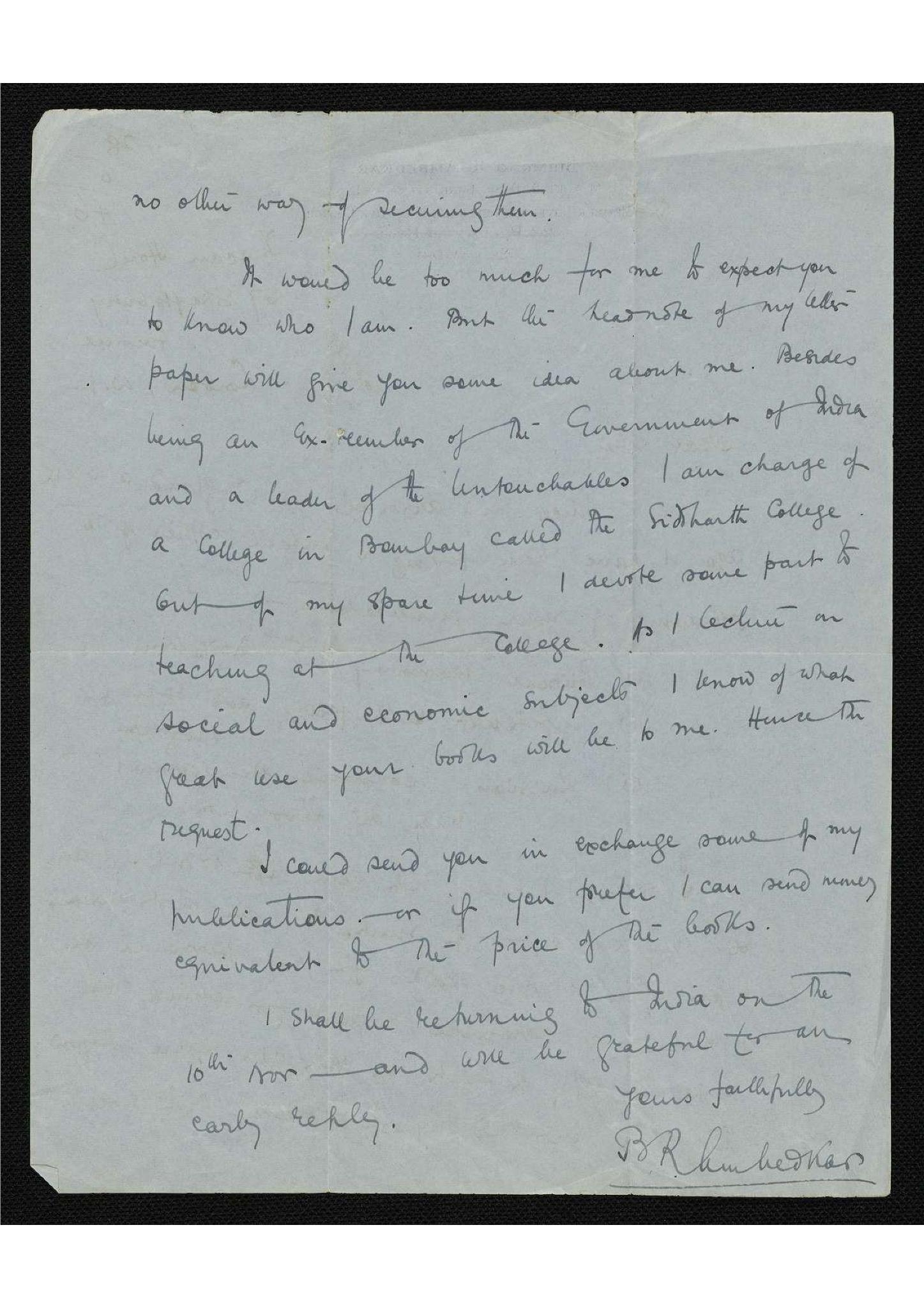

The letter dated 28th Oct 1946, written from the Tuscan Hotel in London, after a week of stay, shows Dr. Ambedkar, having been unsuccessful in finding Dobb’s books, proceeded to drop an “anxious” and “odd” request: copies of publications from Dobb, the author himself, that have gone out of print! He then offered to pay in exchange with his own books or the price equivalent to it, seeking an early reply due to his return to Bombay (planned 10th Nov), after offering an introduction of his credentials - Ex-member of GoI, leader of the Untouchables, in-charge of Siddharth College in Bombay, and of devoting spare time teaching at the College social and economic subjects. This letter was sent only a day before Dr. Ambedkar sent a letter to Bhaurao Patil (BAWS Vol. 22).

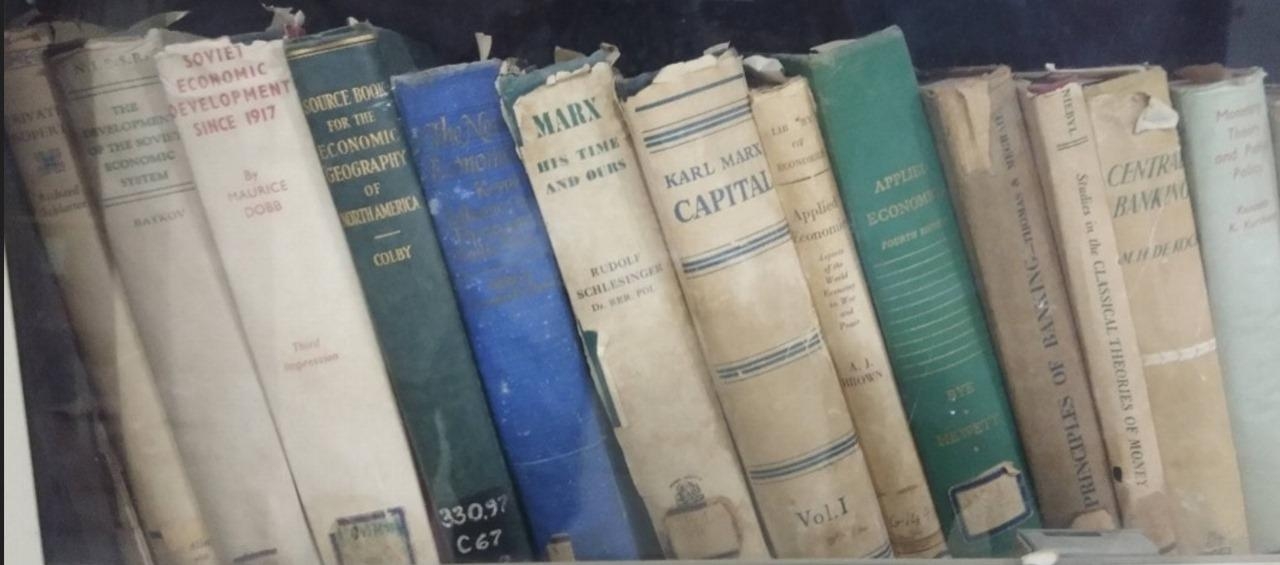

The three books that Dr. Ambedkar mentioned were published in 1925 (Capitalist Enterprise and Social Progress), in 1928 (Russian Economic Development Since the Revolution), and in 1937 (Political Economy and Capitalism). It would have been interesting for him to see the trajectory of this economist who was by then an expert of Soviet economics. Unfortunately, those books had gone out of print by then.

What could have triggered him to look specifically for Dobb’s book? Dr. Ambedkar was a keen reader of newspapers and would often try to fetch the new publications being advertised (see his letters from Vol. 22 and National Archives of India, for reference). Perhaps, it was from one of the reviews (periodicals from America were available in the public library of Baroda too, let alone Bombay, as known from another newspaper)? We see the 409 page long Capitalist Enterprise and Social Progress advertised in Times of India (Oct 5, 1925, pg. 4) as being sold for Rs. 10-15. And after that, the 415 page long Russian Economic Development since the Revolution being acknowledged as “Received” by Times of India (Feb 24 1928 pg. 5) and being priced at 15 shillings. Then we see the same with Dobb’s book, Political Economy and Capitalism being advertised by Times of India (Oct 8, 1937 pg. 8) as having been received - from the authors via their publishers, for possibly offering a Review in the newspaper, in exchange - by Routledge and sold for ten shillings and six pence (10s 6d). Although not being specifically sought by Dr. Ambedkar, the Soviet Russia and the World, from Maurice Dobb’s works, was listed in Times of India (Sep 23, 1932, pg. 1) under “New Books” section.

It might be worth getting a feel of the book from its early reviews on the assumption that such might be along the same lines as what Dr. Ambedkar might have read, before trying to get his hands on it, although his understanding and interpretation is not my cup of tea as I’m not trained in social sciences, let alone a dense subject like Economics, to any degree whatsoever.

It is not a fanciful thought but a well-documented fact that whenever Dr. Ambedkar found himself in London, he would go shopping for books on various topics.

The Harvard economic historian Abbott Payson Usher in the journal The American Economic Review, in its Vol. 16, No. 2 (Jun 1926) reviewed Dobb’s Capitalist Enterprise and Social Progress as thus: “This interesting study is original in the best sense of the word: it presents a fresh view of much discussed material, and yet the new analysis is so carefully tied into the existing body of doctrine that one is scarcely conscious of the essential novelty of the primary positions…He uses the term monopoly in a somewhat wider sense than is common...supply of educated ability which are due to the influence of social institutions. This type of monopoly, called by Mr. Dobb institutional monopoly, has been in his opinion largely neglected in the formal analysis of classical economics...the facility of supply is small because the number of potential entrepreneurs is restricted within relatively narrow limits by a number of highly diversified factors; the scarcity of natural ability; the obstacles created by the expense of training; the necessity of possessing capital and influence in order to start an enterprise; the restriction of the knowledge of the best opportunities to, a relatively small group; the intrenchment of vested interests by legal privileges…In the analysis of modern classes, Mr. Dobb happily breaks away from the socialists' tradition which has for so long identified the capitalists with the middle class. He distinguishes the large from the small entrepreneurs and takes the position that the characteristic problems of the capitalist class are confined to the relatively small group of large entrepreneurs; they constitute a sort of upper class, which takes the place in society formerly occupied by the landed aristocracy... The brilliance of this new grouping of the classes is most strikingly emphasized by the characterization of the "middle class": a ‘motley collection of groups’ without ‘spiritual unity’ whose name plays ‘the same roll that the label 'miscellaneous' plays for the baffled cataloguer’...”

Similarly, a review in the Political Science Quarterly (Vol 44, No. 4, Dec 1929) of Russian Economic Development Since the Revolution by a Columbia University professor (later Professor Emeritus, Economics) who himself served in the Russian Army during the First World War, Michael T. Florinsky, begins decrying the apprehension one has when opening a book on Soviet economics, of which there is no dearth, despite their “small scientific value,” except “Dobb had nothing in common with those generalizations”: “.. it will probably be no exaggeration to say that it is by far the most valuable contribution on the subject which has so far appeared in the English language…Under the able pen of Mr. Dobb the extravaganzas of the Soviet economic policy appear in their natural setting and acquire a kind of internal logic..After an interesting sketch of the economic background of the Soviet state, Mr. Dobb proceeds to show the evolution of Soviet economic policy from 1918 to 1926. The chaos of the first eight months of the Bolshevik Revolution and the resulting economic decline taught the responsible leaders of the Communist Party that a system of "war communism" could not be carried on indefinitely. This principle was not recognized without a struggle within the party itself. But the break between the town and the village was so complete and the danger of open rebellion and actual starvation so serious, that the government had to follow, not without regret, the New Economic Policy forced upon it by Lenin. This was a turning-point in the history of Soviet Russia…Much more convincing is his conclusion as to the immense importance of the ‘new social equality which undoubtedly exists in Russia’ and which " is something more fundamental than the measure of social equality which, in contrast to Europe, is said to exist in the New World..The general impression which one gets from reading the book is that the Soviet government has displayed much greater ability in adapting itself to a hostile environment and changing conditions than it is usually credited with; and that it has behind it a ‘new spirit of creation’..”

Lastly, The Economic Journal (Vol 48, No. 189, Mar 1938) presents a short review from a Scottish economist L. M. Fraser: “This volume comprises eight inter-related essays, four of them concerned primarily with the historical development of value theory, while the remainder deal with various aspects of the conflict between Capitalism and Socialism. Mr. Dobb writes as a Marxist - but, unlike most Marxists, he follows his master in attaching importance to an accurate understanding of bourgeois economic thought. His book is genuinely illuminating, both as to the doctrines of the classical economists and Marx and also as to problems now at issue…”

Surely, the perception of the book in America might have been different from that in Europe and certainly different in India where Dr. Ambedkar might have come across them - but we still get a fair picture of what the books were about, despite having such interesting reviews from the Western elites about the Soviet economy.

Perhaps, the interest in Soviet economics was indeed dying down in the capitalist West, as one reviewer pointed out, that such books went out of print. For most people back then, it might have been difficult to separate books of propaganda (to which the likes of aspiring intellectual Mr. Teltumbde, whose confidence is only rivalled by his inaccuracy, would readily subscribe, in the continued pursuit of demonstrating that Dr. Ambedkar was insufficiently acquainted with Marx) from serious academic study (the book reviews attest to this fact), to which the economist in Dr. Ambedkar would have subscribed. However, it probably did not escape his eye, having seen this name come up from time to time - not only in newspapers - but, perhaps, other academic works referring to it. This must have piqued his interest in securing these books. His interest in Soviet economics wouldn’t fade and he would also later acquire The Development of the Soviet Economic System (1947) by Baykov Alexander as documented by Mangesh Dahiwale and provided to me by my kind friend Dr. SPVA Sairam (who had it in his possession since some time) from the corners of the Siddharth Library. However, what eagle-eyed Dr. SPVA Sairam spotted - and this pleasantly surprised us to no end - was that one of the books (then 18 years old) that Dr. Ambedkar requested, was indeed found to be in his library! That, perhaps, Dobb did send it afterall. This might be the story of how a book that was out-of-print ultimately landed up in Bombay! I’m very thankful for him for providing a closure to this wonderful story since this is the only letter we have been able to find between them. The preservation of Dr. Ambedkar’s side of letters has been neglected purposefully by various Governments, for far too long, and there was little to no chance of recovering a response letter of Dobb from there, if there was one accompanied. One wonders whether we could find copies of Dr Ambedkar’s publication, that may have been sent in exchange, in the collections of Dobb? Unfortunately there is little trail of where that ended up through his will and the estate. Perhaps, one day we might settle this.

Maurice Dobb’s connection to India did not start with teaching Dr. Amartya Sen (who only enrolled into Trinity in 1953). It was more personal. His travel to India in early 1951 was documented quite well. On the morning of 6th January 1951, Mr. and Mrs. Dobb (who was a “television artiste”) arrived in Bombay from London via the RMS Stratheden ship (Times of India, Jan 7 1951, pg. 5). He was a visiting professor to the Delhi School of Economics for the term ending in March and his visit was sponsored by the Reserve Bank of India. Upon his arrival he commented on television sets being increasingly manufactured on a large scale and becoming a popular medium of education and entertainment. Mrs. Dobb’s brother, otherwise known to his Hindu friends as “Sri Krishna Prem,” was living as a “Sanyasi” in Almora, having lived in India since “several years ago” when he first visited there and was attracted by “Indian mysticism”. Later during the trip (ToI, March 19, pg. 9), he also visited University of Bombay to deliver a public lecture on the evening of 20th March in the Lecture Hall of the University School of Economics and Sociology, the subject of which was “Postwar Reconstruction in Soviet Russia”. The presiding Professor for this lecture was none other than Prof. C. N. Vakil who was the University Professor of Economics (contemporaneous student at LSE with Dr. Ambedkar). A summary report of this lecture by the Times of India (March 21), said that “...the Government of the U.S.S.R. had more than achieved most of the targets set in the five-year plan formulated immediately after the war. Russian economy…had now reached the pre-war level and, in some spheres, especially agriculture, steel and coal, the level of production had not only topped pre-war figures, but had exceeded them. For the coming years…a series of ambitious hydroelectric irrigation canal projects and plans for "shelter-belts" of forests to protect crops, - ‘the Stalin Plan for transforming nature' - had been drawn up and some of them already initiated. In the circumstances..it would be wrong to say that the Russians were running an arms race, particularly, when they were agonisingly hoping that another war would not interrupt their plans to raise the level of per capita output in all spheres of production to a degree higher than that prevailing in the democracies of the West….that the outstanding features of the "Stalin Plan" for the coming years were the construction of two canals - the Volga-Don canal which will connect the Baltic and the Black seas and the Oxus River-Caspian Sea canal, which will bring under cultivation vast tracts of the steppe now almost desert…”.The summary caused a clarification to be issued to ToI by Mr. Dobb himself (Mar 23) about the pre-war level being underestimated as he had only referred to figures from 1948 and not 1950, where the Russian pre-war economy was actually 74% higher. Whether Dr. Ambedkar found time and opportunity to meet Dobb (in Delhi or Bombay) while working intensely on the Hindu Code Bill is anyone’s guess.

Dr. SPVA Sairam reminds me of what Dr Ambedkar said in Buddha vs Karl Marx:

“It has been claimed that the Communist Dictatorship in Russia has wonderful achievements to its credit. There can be no denial of it. That is why I say that a Russian Dictatorship would be good for all backward countries. But this is no argument for permanent Dictatorship. Humanity does not only want economic values, it also wants spiritual values to be retained. Permanent Dictatorship has paid no attention to spiritual values and does not seem to intend to. Carlyle called Political Economy a Pig Philosophy. Carlyle was of course wrong. For man needs material comforts. But the Communist Philosophy seems to be equally wrong for the aim of their philosophy seems to be fatten pigs as though men are no better than pigs. Man must grow materially as well as spiritually. Society has been aiming to lay a new foundation was summarised by the French Revolution in three words: Fraternity, Liberty and Equality. The French Revolution was welcomed because of this slogan. It failed to produce equality. We welcome the Russian Revolution because it aims to produce equality. But it cannot be too much emphasized that in producing equality society cannot afford to sacrifice fraternity or liberty. Equality will be of no value without fraternity or liberty. It seems that the three can coexist only if one follows the way of the Buddha. Communism can give one but not all.”

Humanity does not only want economic values, it also wants spiritual values to be retained... Man must grow materially as well as spiritually.

Much earlier in 1947 too, one can see Dr. Ambedkar’s work “States & Minorities” envisioned a form of state socialism with the “..key industries…agriculture…shall be owned and run by the State”. Dr. Ambedkar’s interview from 1953 also showed him having to lean on “some form of Communism” as an alternative to the sham of perpetual elections and democracy that Congress and the ruling castes had made, in order to provide the “material needs” of the masses, which included “agricultural lands”. His views, and therefore his lectures at the Siddharth College (which he refers to in his letter to Dobb, in which he would find “a great use” of Dobb’s books, as the reason for his seeking his publications) could not have been supported without a deep study in Marxism and its practical demonstration through a study on Soviet economy - for which works of Dobb might have been helpful given that Dobb was singularly credited with doing the most to bring Marxist ideas into the mainstream narrative by showing “the other side”.

I wonder what Dr. Amartya Sen would say about these new revelations of correspondence between whom he considered (and we share that belief) his father of economics and whom he remembered as his teacher at Cambridge. I hope that delving into such lost stories makes us realise that the great library Dr. Ambedkar built, was not only thoughtfully curated, but could contain books collected from other important personalities of his time. It was his parting gift to us and we must treat it as such.