Babu Mangu Ram, born in 1889 in Punjab’s Hoshiarpur district (the same region from which Manyavar Kanshiram later emerged) led the Scheduled Castes of Punjab in a saga of dignity from 1926 to 1952 under the banner of the new religious movement, Ad Dharm.

Unfortunately, despite his epoch-making contributions, he was largely ignored by academia and historians of the time, leaving behind only a limited body of scholarly work. Most notably Mark Juergensmeyer’s Religious Rebels in the Punjab: The Ad Dharm Challenge to Caste, along with select writings by Ronki Ram and D. C. Ahir.

Although Dr. Ambedkar and Mangu Ram were contemporaries, working toward a common mission during the same period, no documentary evidence exists to suggest that both these great personalities ever crossed each other's path. However, although they never met, their ideological trajectories intersected on multiple occasions, which this article attempts to explore in detail.

To set the context, we need to understand the radical idea of a new quam (new identity), the emergence of the Ad Dharm movement, and the early life of Mangu Ram.

Formative years of Mangu Ram

Mangu Ram's father, Harman Dass, had given up the caste-bound occupation of tanning and was Ravidasiya panthi. Interestingly, Babasaheb Ambedkar's father, Subedar Ramji Sakpal, was a Kabir panthi. Ravidas and Kabir, both medieval contemporaries, articulated a radical cultural revolt of caste through the Bhakti tradition.

Mangu Ram was born in Mugowal in the Doaba region of Punjab, a region that later emerged as a major hub of the anti-caste movement. His early education came from a village sadhu (saint) belonging to the Ravidas tradition, after which he pursued formal schooling at a high school in Bhajwara. Like Babasaheb Ambedkar, Mangu Ram faced caste-based humiliation in school. He was made to sit separately, often outside the classroom, on a gunny bag that he had to bring from home.

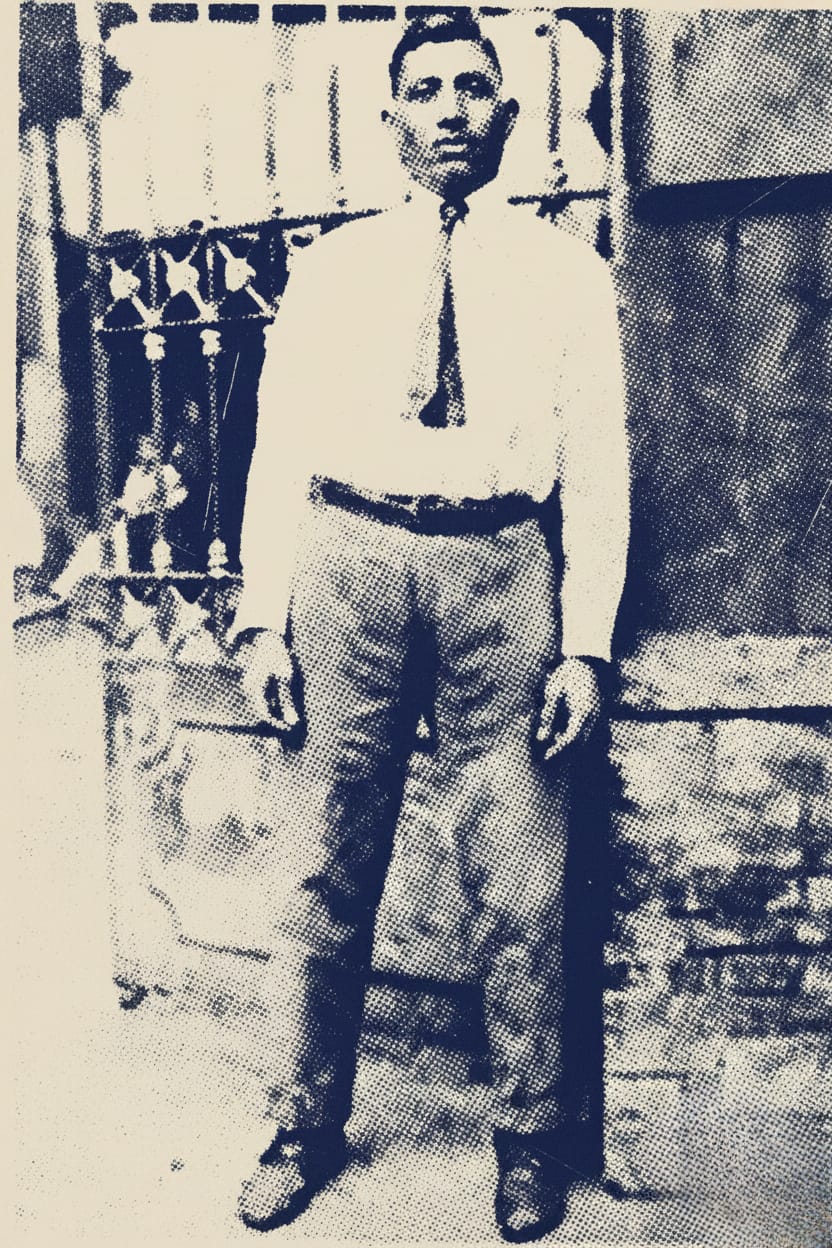

A young Mangu Ram Mugowalia, whose time abroad shaped his vision for liberation.

In 1909, influenced by his peers in Doaba, Mangu Ram left for the United States in quest to escape the brutal caste realities and possibilities. Yet, even in America, for survival he had to labor on the farm of a Punjabi zamindar who had settled in California.¹

In the foreign land, Mangu Ram still found a measure of solace, as caste realities did not confront him with the same intensity. After sixteen years abroad, when he returned to Punjab, he was shattered to find Indian society like still water and growing more rotten with time. He wrote:

“While living abroad I had forgotten about the hierarchy of high and low, and untouchability; and under this delusion returned home in December 1925. The same disease from which I had escaped started tormenting me again. I wrote about all this to my leader Lala Hardayal Ji, saying that until and unless this disease is cured, Hindustan could not be liberated. In accordance with his orders, a programme was formulated in 1926 for the awakening and upliftment of the Achhut qaum (untouchable community) of India.”²

This was the moment that struck the fire in the heart of Mangu Ram that later emerged in the Ad Dharm movement and him as cult figure for the Scheduled castes in Punjab. One can draw the parallel from Dr. Ambedkar when he returned to India and encountered the same caste realities which compelled him to take the sankalp (pledge) to throw the stigma of untouchability and caste from the very face of India.

Need of new identity and emergence of Ad Dharm

In early 20th century of Colonial India, while the rest of the Indian mainstream political stalwarts were fighting to root out the British imperialism, the leaders and movements emerging from lower castes and the scheduled castes sees the British time has a buffer time to reform the society. Be it early Phule-Shahu-Ambedkar movement from Maharashtra, Iyothee Thass critque of Swaraj reform from Tamil Nadu, Namoshudra movement in West Bengal and Ad Dharm movement from Punjab. “The ultimate result was neither the Nehurivan secularism nor Gandhian 'Ramraj' could provide an Indian identity that was liberatory for the Dalit and low castes...” (Omvedt, 1994)

Punjab presents a peculiar case. The region witnessed the presence of several communal organisations that of the Arya Samaj, the Christian Church, the Sikh Khalsa Diwan, and the Ahmadiyya (muslim outfit). With the introduction of separate representation under the Morley–Minto Reforms of 1909, later formalised through the Government of India Act of 1919, an atmosphere of anxiety emerged among these groups as each sought to demonstrate numerical strength. The Scheduled Castes constituted nearly one-fourth of Punjab’s population. As a result, these organisations began actively wooing the Scheduled Castes to gain a numerical edge. In the absence of an independent organisation to articulate and protect their interests, the Scheduled Castes became the focus of this aggressive mobilisation. The Arya Samaj, in particular, launched shuddhikaran campaigns aimed at bringing Scheduled Castes and Shudras into the Hindu fold back from Sikh, Muslim, or Christian.

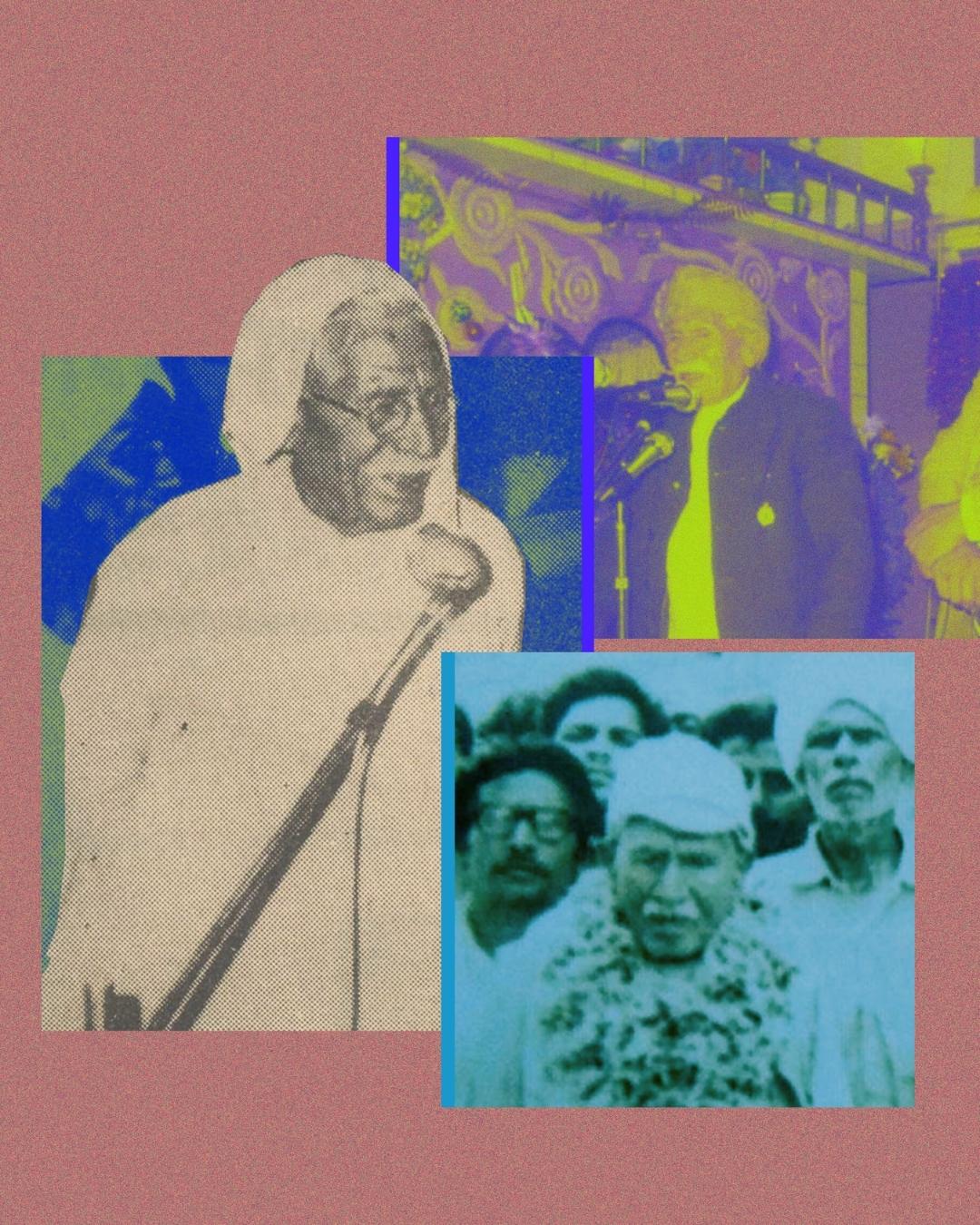

Babu Mangu Ram Mugowalia (wearing white cap) with members of the Ad Dharm movement.

At this juncture, Mangu Ram saw this as opportunity and need of the hour and began taking his ideas literally to the doorsteps of the Scheduled Castes in the Doaba region and, in a short time, emerged as a hero of the community. His agenda was clear: to create a new identity for the lower castes, one that was not only of political importance but also religious. Ad Dharm (Ad, meaning ‘original’ or ‘inhabited’, religion) was central to this vision. It was conceived as the ancestral religion of the lower-caste communities, one that had been colonised by Aryan–Vedic imperialism. His idea drew upon idol figures such as Ravidas Maharaj, Sant Kabir, Sant Namdev, and Bhagwan Valmiki, among others.

At the first annual meeting of the Ad Dharm movement, Mangu Ram issued a clarion call to his quam. The gathering brought together members of several Scheduled Caste communities. As Ronki Ram notes, these included Ravidasiyas, Chuhras, Sansis, Banjharas, and Bhils. Addressing them as brothers, Mangu Ram declared:

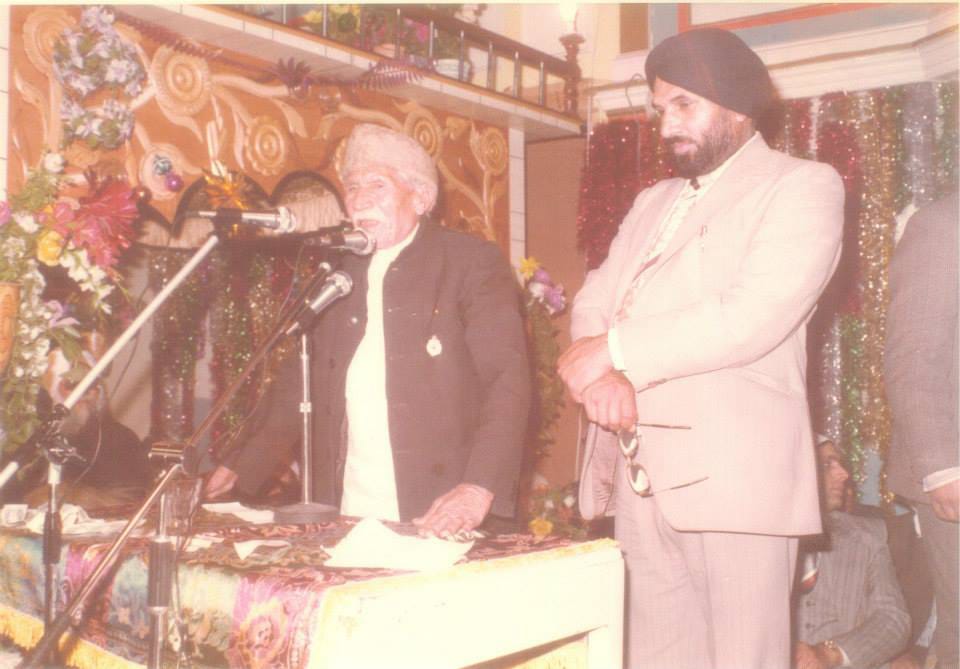

A clarion call to the Quam: Mangu Ram addressing his people.

“They (caste Hindus) deprived us of our property and rendered us nomadic. They razed our forts and houses, and destroyed our history. We are seven crores in numbers and are registered as Hindus in this country. Liberate the Adi race by separating these seven crores.

They (Hindus) became lords and call us ‘others’. Our seven crore number enjoys no share at all. We reposed faith in Hindus and thus suffered a lot. Hindus turned out to be callous. Centuries ago, Hindus suppressed us; sever all ties with them. What justice can we expect from those who are the butchers of the Adi race? The time has come; be cautious, now the Government listens to appeals. With the support of a sympathetic Government, come together to save the race. Send members to the councils so that our quam is strengthened again. British rule should remain forever. Make prayer before God. Except for this Government, no one is sympathetic towards us. Never consider ourselves as Hindus at all; remember that our religion is Ad Dharm.”³

Much of what Mangu Ram says here is also found in Dr. Ambedkar’s What Path to Salvation. This ideological parallels between this speech and What Path to Salvation are striking. Like Ambedkar, Mangu Ram emphasized the necessity of conversion, the need of new identity out of Hindu fold through ‘change in name’ and a ‘change in religion’ as prerequisites.

After this speech, Ad Dharm took root among the Scheduled Castes of Punjab. Members of different communities began recognising one another as Ad Dharmis, greeting each other with ‘Jai Guru Dev’ and ‘Dhan Guru Dev’. The Gurmukhi phrase Sohang (‘I am that’) emerged as a central mantra of the Ad Dharm faith. The community also adopted its own calendars, marking significant dates. This period marked the institutionalisation of Ad Dharm as a distinct religion.

“When the social reformer challenges society there is nobody to hail him a martyr. There is nobody even to befriend him. He is loathed and shunned.”

— Dr. Ambedkar⁴

The same pattern appeared in the case of the Ad Dharm movement. Violence followed against its leaders and followers, who were chased and attacked by Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim outfits. Jat Sikh landlords imposed boycotts, denying Ad Dharmis access to common lands where they had earlier grazed their animals. Many were looted and publicly humiliated. Caste villages enforced organised social boycotts against the new quam.

In several areas, Jat Sikhs pressured Ad Dharmis to record themselves as Sikhs. In Rajput-dominated villages, the water pitchers of Ad Dharmis were smashed, denying them access to common water sources. Youths were abducted from public meetings. The ongoing torture forced many Ad Dharmis to leave their villages altogether.

Despite this brutal repression, the community largely remained intact. Only a few leaders broke away, aligning themselves with the Arya Samaj and other outfits. While the community still registered Ad Dharm as their new religion.

The communal award and Poona Pact

After years of struggle led by Dr. Ambedkar, and following his bitter experience with the Congress and Gandhi at the two Round Table Conferences, the British agreed to award separate electorates to the Scheduled Castes. This was a path-breaking achievement, offering the community a rare moment of political assurance and a measure of institutional protection for the future.

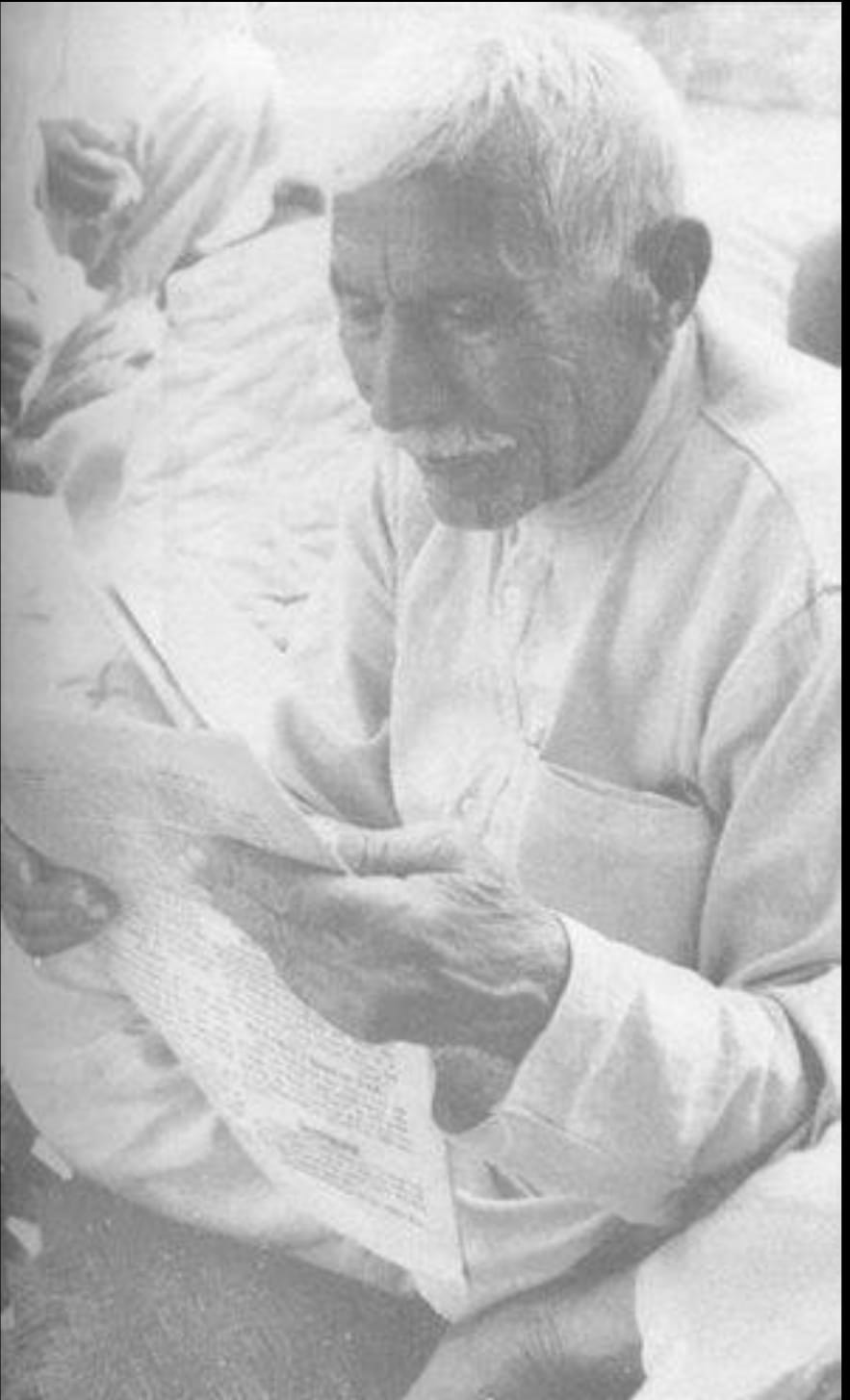

A reflective moment: Mangu Ram studying documents.

However, Gandhi strongly stood on his opposition to the provision of separate electorates and began a fast unto death against it. This decision pushed the country into turmoil and placed immense pressure on Dr. Ambedkar. Writing in her autobiography, Dr. Savita Ambedkar recalls:

“Gandhiji, who had gone to attend the Round Table Conference to discuss the entire country, came back with the single plea that the untouchables should not be granted an independent constituency. This was not merely surprising, but also an extremely unfortunate episode. Since it became a life-and-death question for Gandhiji, the entire country was naturally thrown into turmoil. Tension and worry spread everywhere. While it was Gandhiji who was doing the fasting, really speaking it was Dr Ambedkar's life that was in bigger danger. He began receiving threatening telegrams, letters and telephone calls from every corner of the country. Some opponents went to the extent of sending their threats written in blood. Instead of saying that an anti-Ambedkar atmosphere spread across the country, it would be more appropriate to say that an anti-Ambedkar atmosphere was deliberately created across the country.” ⁵

At a moment when much of the country had turned against Dr. Ambedkar, Mangu Ram of Punjab took a radical stand. He swiftly announced a parallel fast unto death in response to Gandhi’s fast. Declaring his position, he said: “If Gandhi is prepared to die for his Hindus, then I am prepared to die for these untouchables.”⁶

This counter-fast, admittedly carrying an element of political theatre, formed part of a broader effort by Mangu Ram to mobilise support for Dr. Ambedkar’s position. Mangu Ram even went on to write letters to the then Monarch of Britain, King George, and threatened the British with massive disruption throughout Punjab.

He later recalled that he told the British he had complete control over the Untouchables of the Punjab: "They were willing to die for me if necessary" (Mark Juergensmeyer, 1988). In this charged atmosphere of anti-Ambedkar mobilisation, Mangu Ram publicly declared Dr. Ambedkar as his national leader, offering him moral and political support at a time when Ambedkar stood increasingly isolated.

Unfortunately, as the history witnessed, Dr. Ambedkar in pressure took a pragmatic step and signed the conditions of Gandhi under Poona pact. Mangu Ram was upset by this step and called it a great blunder. He continued his fast even after Poona Pact and broke it only after the declaration by the government that eight seats would be reserved for the untouchables in punjab.⁷

Despite the Poona pact episode and other episodes, he succeeded in institutionalizing the Ad Dharm as a separate religion before the state in 1931 Census. In 1950, Mangu Ram requested his Quam to relieve him of active social service life and called upon young Ad Dharmis to take forward the cause.⁸

Babu Mangu Ram in his later years, passing the baton to the next generation.

End Notes & References

- Ronki Ram, Interview with Chattar Sain

- Ronki Ram, Interviews: Chanan Lal Manak, Jalandhar, 1 May 2001; KC Sulekh Chandigarh, 1 July 2001.

- The text is in the form of poetry (in Punjabi). Translated by the author and Seema Goel

- BAWS Vol 1, (Link)

- Babasaheb: My Life With Dr. Ambedkar, 2022

- 6, 7, 8. Ronki Ram, Mangoo Ram & Ad Dharm, the Dalit Movement in Punjab

Selected Readings

- Mark Juergensmeyer, Religious Rebels in the Punjab: The Ad Dharm Challenge to Caste

- Ronki Ram, Mangoo Ram & Ad Dharm, the Dalit Movement in Punjab

- Selected Writings of D.C Ahir