During the second round table conference in London, when Baba Saheb Ambedkar was trying to strongly claim a separate political minority status for the untouchables apart from the Hindus, he received telegrams from many untouchable organizations supporting him as the leader. Prominent among them was the Ad Dharmi Samaj from Punjab who too strongly wanted to not count themselves as not Hindus. Later in 1935, Baba Saheb at Yeola once again reiterated the claim to not be Hindus in a religious sense. These claims to be separate from Hindus in the public sphere stirred such a national debate that Gandhi had to accelerate his “pro-harijan” activities and utterances, Savarkar couldn’t help but to write bitterly against this move and leaders from various religious communities wanted to approach him.

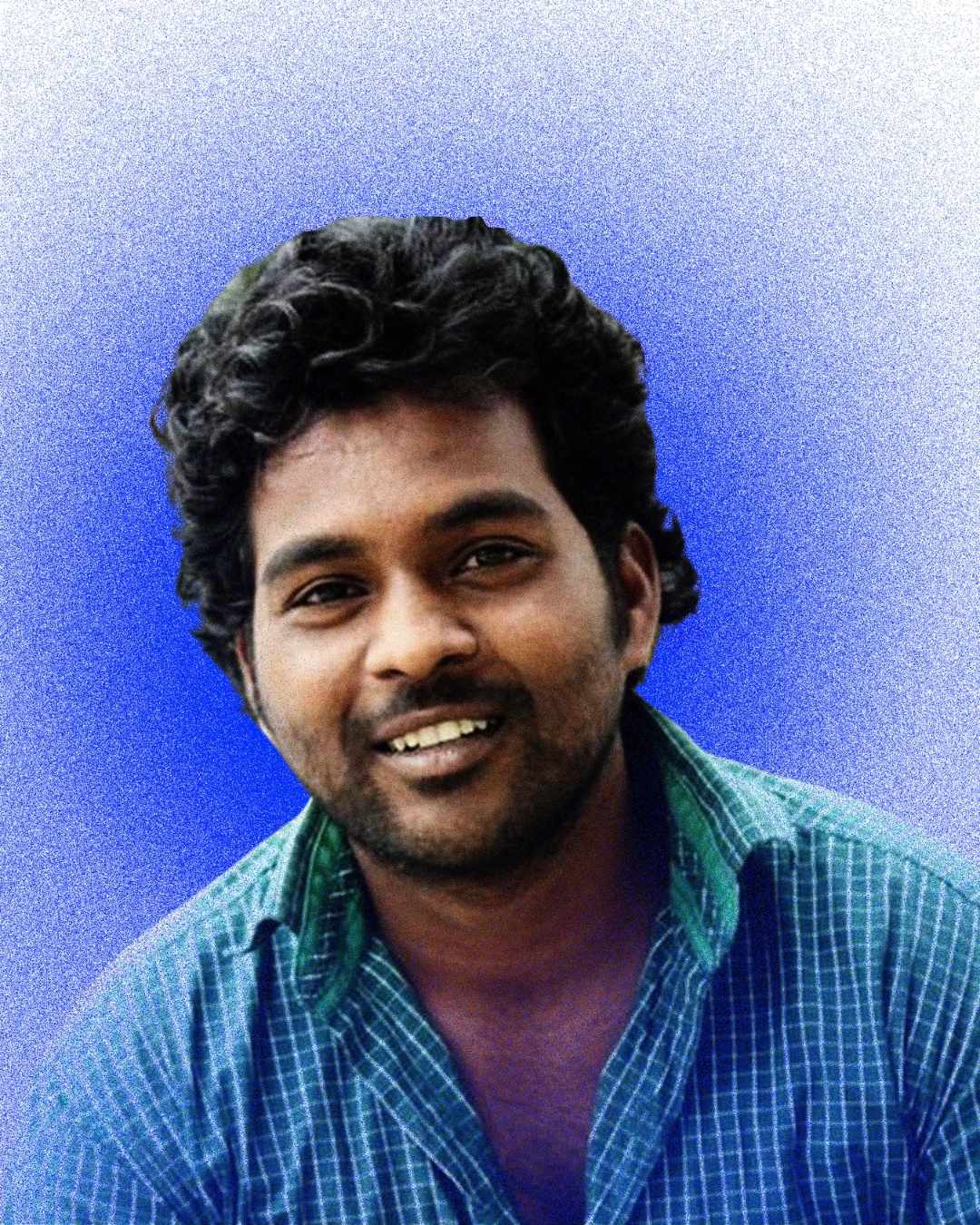

Decades later in the 1980s and 1990s, when Kanshiram Saheb, the founder of Bahujan Samaj Party worked towards consolidating lower castes and Dalits in unsettling decades of upper caste power in electoral politics, a similar stir was felt in the public sphere. You may be wondering why am I reviewing this history in remembering Rohith’s 10 years death anniversary? Rightly so, especially when Rohith’s story has been familiarised over the last many years not within the larger political history of Dalits but within tropes of institutional discrimination, struggles of a Dalit life, a campus activist and many a times sensationalism portrayed through a voyeuristic gaze that reduces him as a symbol as one fits. Yes, institutional discrimination is rampant in overt and covert ways in educational institutions, and yes lives of the majority of Dalits are not easy and Yes Rohith was an assertive student activist. But the loss of Rohith was also a moment that catapulted the discussion on caste to the public sphere in India which was also a legacy of Rohith’s activism in the HCU campus that inspired many Dalit-Bahujan youths and community organizers to come out to the streets. However, it is also important to remember that there were many actors to whom the exigencies of speaking about Rohith in public also emerged out of a particular political moment, a stage of digital media penetration, influence of liberal identity discourse, caste correctness and that also shaped the “Caste Slot” Post-Rohith.

I borrow the term Caste Slot from Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s concept of “Savage Slot” by which he argues that European colonization had a savage slot in defining the tribal communities from the earlier period in 16th century and which was filled by fantastical literature, travel accounts before anthropology took its place in 20th century. Similarly, I argue that the public sphere dominated by upper castes in India has a “Caste Slot” by which they decide when caste can be spoken and how it will be spoken. There is a pattern to it; when the judiciary gives any decisions with regards to caste, when election approaches and at times when gut wrenching violence is unleashed on Dalits and large protests erupt. The “Caste slot” during Rohith movement falls in the third category.

I will not be repeating the sequence of events followed in Hyderabad Central University Campus in 2015-16, the role of Smriti Irani, Bandaru Dattatreya, Appa Rao and ABVP in stifling and antagonising Rohith during and after that heart breaking night of January 17. There are many writings available in public from students who were present in HCU and participated in the protests. I am also not looking at how institutional discrimination happens against Dalit-Bahujan and Adivasi students in university spaces, there is quite a few materials on it. Rather, in this article, I want to explore what happened to the “Caste slot” after Rohith and where do we place this in the political history of Dalits. Because this moment was not isolated nor it was made to be unlike earlier cases of institutional discrimination against Dalit students. The aftermath of January 16 became one of the defining moments in the political history of Dalits, student activism and articulation of caste. In both of the earlier moments that I referred to in the case of Baba Saheb Ambedkar and Kanshiram Saheb, these two figures articulated and mobilized around caste in a manner that has had lasting impact for the Dalit Bahujan communities in the course of Indian history and the present. There are other moments like the Dalit movement in the then Andhra Pradesh in the 1980s whose protests against caste massacres led to the SC/ST POA.

Rohith’s political activism during his final years happened during the early years of BJP and many different political groups and civil society had started to share the imminent threats from Hindutva. This was a time when digital media had become far more penetrated than before with alternative media platforms emerging, many of whom have had a long left-liberal lineage. This is also a time a few years after Black Lives Matter and the notion of an individual identity and the need to self-fashion oneself around it was gaining ground in urban educational institutions and cultural circles. The last time before this there was a “caste slot” in the English public sphere, it was BSP coming to power in Uttar Pradesh in 2007, where for the next few years Behenji Mayawati had become an object of ridicule, ruthless criticism and backhanded comment by the Delhi media as well as by the upper caste artists and middle class.

The public sphere dominated by upper castes in India has a “Caste Slot” by which they decide when caste can be spoken and how it will be spoken.

This time, for the alternative media, Rohith was to become an aid in their critique of BJP and Hindutva and also their claim to being pro-dalit. The same media and civil society had lambasted Dalits just two years before by blaming them for the coming of BJP and hardly discussed any event questioning caste power. But Rohith movement became an opportunity to utilize the “Caste Slot” to criticize BJP without further engagement with any structural questions around caste including the efforts to establish anti-discrimination cells in and demand stricter laws against caste discrimination of Dalit and Adivasi students in colleges and universities. The Dalit student groups after initial vigor in protests and mobilizations could not but dissipate and it has usually been the nature of Dalit protests due to their lack of resources, vulnerability in the face of hostility and struggles for life. Radhika Amma kept going and continues to go from one place to another in solidarity and speak for many structural changes for Dalits as a community. It has been ten years now and why did this moment, despite becoming so big with widespread mobilizations, could not lead to formulation of any coherent critique of caste power and a way forward for Dalit students in particular and Dalits in general?

One definitely has to reckon that those who regulate the “caste slot” allow what they want the public to hear and that many came because of their opposition to BJP. Some came to express solidarity to Rohith movement but it was to be for a brief moment even if with a good faith.

However, one also has to ask what happened from the side of Dalits who were better placed than others to articulate any meaningful way ahead. I believe the influence of individual liberal identity politics from the West and transitory euphoric moment engagement tendencies prevented this small section in generating any meaningful discourse for Dalits. Those aloof from community due to their life histories, did not have the depth to imagine, the familiarity of community and the conviction to articulate a coherent critique of caste power. Furthermore, the small section of heart changed upper castes did not do much beyond following a DEI model where now they had to invite one Dalit, one OBC to events and to know of experiences so others can sympathise. Dalit led political parties, although raised their voice initially, receded back gradually by not utilizing the momentum gained in order to create or push for any policy level changes for educational institutions in particular and Dalits in general.

Those who took many videos of Rohith protests, wrote articles, fetishized his letter, aestheticized his life through painful tropes gradually moved on to something else. It was an euphoria, an urgency to do something out of it, a transitory moment to only be forgotten behind. It was not a deep conviction, nor placing it as a moment in the political history of Dalits to take it forward. Although not all is bleak in the end, a group of Dalit students from Karnataka quietly worked to push for Rohith Act in higher educational institutions, the Ambedkarite students kept his memory alive year after year, so many Dalit students from difficult life backgrounds across India came to articulate caste in public, wanted to know more, be politically more aware, connect with their community members and wanted to expose themselves with greater confidence and wanted to pursue higher education.. Maybe this is Rohith’s legacy that we can hold on to in the meantime and whenever someone from our community succeeds after crossing many barriers we can be proud and back them up. It is a hostile world out there and a community is all we can build to safeguard our people…