For nearly four years, Mumbai has lived without an elected Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation. This long suspension of local democracy has not only delayed governance, it has reshaped the politics itself. During this time, turmoil change has been experienced by the leaders as well as voters. The split of Shiv Sena into two parties: the Uddhav Thackeray-led Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray/UBT) which has a new symbol of Mashaal (Torch) and Eknath Shinde-led Shiv Sena (2022–present) which has the original party name and the “bow and arrow” symbol.

The predominant campaign strategy in this election is the language debate or Marathi Asmita. Long before Brihanmumbai Municipality Corporation (BMC) elections were even announced, BJP, both the Sena’s and every party was busy organising rallies, Dasra Melawas, Vijayi Melawas, Shobha Yatras, Ganpati festivals, cultural gatherings and symbolic appearances. These also substituted the basic civic responsibility. Shiv Sena (UBT) and the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) were seen active in this prolonged pre-election phase, preparing from at least 2024 as if the city were permanently in campaign mode.

In a liberal-progressive circle, their union felt as a hope. They mobilised cadres, reminiscing a unity, reclaimed symbolic spaces like Shivaji Park-Dadar, Thane, Worli and Suburbans as the custodians of Marathi pride in a city they claim is losing its soul: the city’s Marathi-ness all declined under their watch. Marathi Asmita was rejuvenated as a dire necessity to reclaim one’s identity. Ironically, the 5-day long hunger strike by Manoj Jarange-Patil, last year in Mumbai, for inclusion of Marathas into OBC category, were not just ridiculed but writ petition filed by gatekeepers of Marathi Asmita for the damage that agitation caused.

In a political climate dominated by hate, this political alliance is celebrated as the “purity of campaigning”. But that idea of purity collapses the moment we look beneath the surface. The Marathi Asmita being mobilised today is not inclusive pride. It is a carefully curated identity, dominated by upper-caste leadership, Maratha historical memory and linguistic hierarchies that decide who speaks for Marathi society and who merely fills the crowd.

Jay Patil, 34, a banker and inhabitant of Mumbai, reflects on the changing nature of the city’s politics. “Just two days ago, Shivaji Park witnessed a powerful rally. Raj Thackeray spoke strongly about how Prime Minister Modi is using his power to support Adani and help him grow. But only a few months back, the same Adani met Raj Thackeray – and those pictures are still circulating. This is what politics has become. Elections are no longer about ideology or loyalty. Whether it is the BJP, Shiv Sena or even Congress and NCP; everyone seems to have surrendered to Adani. Then what is the point of playing the Marathi Asmita card? Even the media is hyping the BMC election, because every major media house is based in Mumbai. But in reality, it feels like the same power operates behind every party”.

Nothing exposes this contradiction more clearly than what happens in Mumbai every December 6th. Mahaparinirvan Diwas at Chaityabhumi is not just a memorial event, it is one of the largest democratic gatherings in the country without built infrastructure or political party supporting it. Lakhs of people arrive not for spectacle but for memory, dignity and political assertion. Vanchit Bahujan Aghadi’s (VBA) youth leader, Sujat Ambedkar, rightly points for hypocrisy of the political parties for subsuming Dalits into the Asmita, who otherwise shame them for their assertion. He calls it, “Manuwadi Marathi behaviour”. He asserts that, “the gathering is treated as an inconvenience. A law-and-order issue. A traffic problem. A mob that must be managed rather than people who must be respected. Never forget casteism in Marathi Asmita.”

This year, leaders of UBT and MNS who live in Shivaji Park deliberately chose not to bother with even a symbolic presence at Chaityabhumi. When officially, protocol demands that the ruling dispensation perform the formalities. Parties that claim to represent Marathi pride showed no urgency in standing with the largest gathering of Marathi Dalit-Bahujan citizens in the city. Their silence spoke louder than any speech at a rally, gatherings.

"The Ambedkarite crowd is tolerated, not embraced. Allowed, not honoured. Managed, not mobilised. Dalit gatherings are permitted to exist but rarely allowed to define the agenda."

It reflects a deeper structure of exclusion that has long defined Marathi politics. Their history is ritualised once a year but their politics is never allowed to become central to Marathi identity. This is where the rhetoric of “ghettoisation of Marathi people in Mumbai” becomes deeply dishonest. Because Marathi society itself is structured by caste ghettos. Those who speak Marathi but come from Dalit-Bahujan communities still face cultural policing, linguistic gatekeeping and political invisibility. Their Marathi is treated as impure. They are told they belong to Marathi Asmita but only on terms decided by upper-caste power.

Anil Pagare, a 37 year old resident of Chembur expressed, “this mindset is not limited to the BJP. It exists across the political spectrum. The discomfort with December 6th crowds is not about administration. It is about caste anxiety. It is about fear of a political assertion that does not seek validation from traditional power centres”.

This fear is not abstract. It is deeply historical.

During the Samyukta Maharashtra Movement, the dominant narrative today celebrates Acharya Atre’s The Maratha newspaper and Balasaheb Thakare’s Marmik cartoons and heroic sacrifice. What it does not remember is the humiliation faced by leaders like Amar Sheikh, Annabhau Sathe and Shahir Gavankar. As if they were not in linguistic unity. They were on the streets, mobilising workers, performing revolutionary cultural programmes, building consciousness among the masses. Yet when it came to the so-called “main meetings”, to spaces where decisions were made and leadership was recognised, they were sidelined. Good enough to inspire, not good enough to decide. “Even though, Mazi Maina – A Chakkad to communicate and mobilise the whole Maharashtra, later considered the powerful voice and inspiration song, at the time of movement were ridiculed”, says poet and writer Nissar Zalte.

That same logic continues today. Dalit-Bahujan voices are welcomed as poets, singers, activists and foot soldiers. Rarely allowed to shape political strategy or define the movement’s ideological direction. They fill the rallies but do not command the stage. They are the energy, not the authority. And when they demand more than symbolic inclusion, they are accused of dividing the movement, weakening Marathi unity or playing identity politics; as if caste power is not already the most entrenched identity politics of all.

This is why the claim of maintaining the “purity of campaigning” feels hollow. A rally can be peaceful and still be exclusionary. A speech can be poetic and still be casteist. The real impurity of politics today is not only in hate speech or riots. It lies in selective inclusion. In deciding who belongs to the centre of politics and who remains permanently at its margins. “For every party, Marathi Asmita has become a convenient vote-bank tool that is sharpened before elections, softened for alliances and diluted in power deals. But it is rarely used to challenge caste privilege within Marathi society. As a result, slogans of Marathi pride feel empty to Dalit and working-class Mumbaikar’s, who still face discrimination, exclusion and everyday humiliation from those who speak the same language but practise a different social morality”, a media practitioner Rohit Pawar based in Thane conveyed in a helpless note.

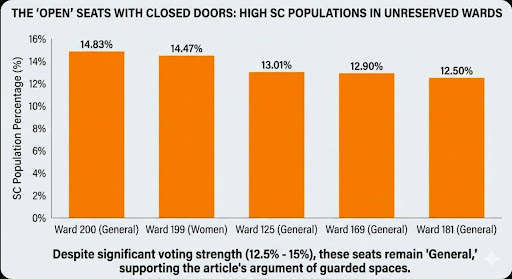

Reservation charts often reveal the guarded spaces of dominance within the BMC.

The reality of Mumbai lies in the chawls-slums and in peripheral suburbs. A folk artist, Rahul Aru from Badlapur said, “the experience of being Marathi is very different from what is projected on political stages. For many Dalit families, Asmita has never guaranteed dignity. They clean the city that others claim ownership over. They build the neighbourhoods that others dominate. On the other hand this hypocrisy is going to stretch more. A city built by mill workers, sanitation workers, dock labourers, domestic workers, street vendors, Dalit organisers and migrant builders always held together by an identity politics that honours only upper-caste heritage and middle-class nostalgia”.

However, the result will decide who controls contracts, budgets and tenders. It will be clear whose Asmita will define Mumbai’s future. If UBT and MNS truly wish to present themselves as alternatives to BJP-style majoritarianism, they must go beyond cultural rhetoric and confront the caste structures embedded in their own imagination of Marathi society. This confrontation will not be easy. It will demand that leaders step outside comfortable narratives of victimhood and nostalgia and ask harder questions about caste privilege. It will demand that Marathi politics should stop pretending that caste is an external problem imported by others. Parties have to acknowledge that the greatest injustice within Marathi society is not done by outsiders but by insiders who monopolise leadership, legitimacy and voice.

Without that reckoning, every gathering, however disciplined, will look alike – politically clean but socially unjust. And Mumbai will continue to live with a cruel paradox: Marathi Asmita on banners and Marathi humiliation on streets. This injustice is proudly displayed on the reservation charts for 227 corporators, quotas for Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, Other Backward Class communities and 114 seats for women. On the ground, it looks like power refusing to move. The truth is simple: while SC, ST and OBC candidates are legally free to contest from general wards, politically those seats remain guarded spaces of upper-caste dominance. Shambuk Sankalpana, a political thinker says, “every party practises that the Dalit-Bahujan candidates are encouraged to stay within ‘their’ reserved constituencies, quietly told where their ambition should end. The moment they step into open wards, they are questioned about winnability and image.”

"This is not cultural pride but a caste power wearing a cultural mask."

Across parties, the pattern is the same. Hindutva, linguistic nationalism, secular rhetoric have different languages and identical outcomes. When general seats function as informal upper-caste preserved, democracy becomes a performance. Marathi Asmita cannot claim dignity while denying equality to Marathi Dalit-Bahujans. If power remains hereditary in practice, then pretending that representation has arrived is causing the Asmita itself.

If the politics of Marathi Asmita continues to be built on selective memory, it will only deepen the fractures it claims to heal. If it continues to limit the Chatrapati Shivaji while ignoring Babasaheb Ambedkar, celebrate pride while silencing caste, and invoke unity while practising exclusion, it will deepen the caste issue which has been bothering the democracy since its inception. On other hand, among the 109 martyrs of the state violence against the Samyukta Maharashtra Movement protestors, there are a majority of Dalit-Bahujan identities, if studied carefully. Marathi Asmita need to address Mumbai’s Dalit-Bahujan and working class voices who toils to function it and not those upper-caste purity imposers chants.