FRAMING THE MARGINS: CASTE ON THE SILVER SCREEN

Cinema is not just entertainment; it is political. From the erasure of Dalit lives to the rise of the anti-caste gaze, we explore how movies uphold or dismantle the hierarchy.

Caste and Cinema

Phoolan Devi: Beyond the Gun and the Gavel

By Ritesh Jyoti

Unfortunately, mainstream discourse has always imagined her life either through the lens of victimization or criminalization.

The Burden of the Enlightened: The Need for Mahar Community to Take Ambedkarite Buddhism Beyond Itself and Lessons from Kanshi Ram

By Saumya Barmate

What good is an emancipatory philosophy that remains confined to the already converted?

Poona Pact: When Punjab Stalwart Mangu Ram declared Dr. Ambedkar as the leader of his new Quam

By Ritesh Jyoti

At a moment when much of the country had turned against Dr. Ambedkar, Mangu Ram of Punjab took a radical stand: 'If Gandhi is prepared to die for his Hindus, then I am prepared to die for these untouchables.'

The Empire’s New Crutches: Disability, Dependency, and the Neocolonial Trade

By Athul Krishna

On December 3rd, the machinery of the global elite will once again grind into gear to perform its annual, sanitized ritual of observation for the International Day of Persons with Disabilities.

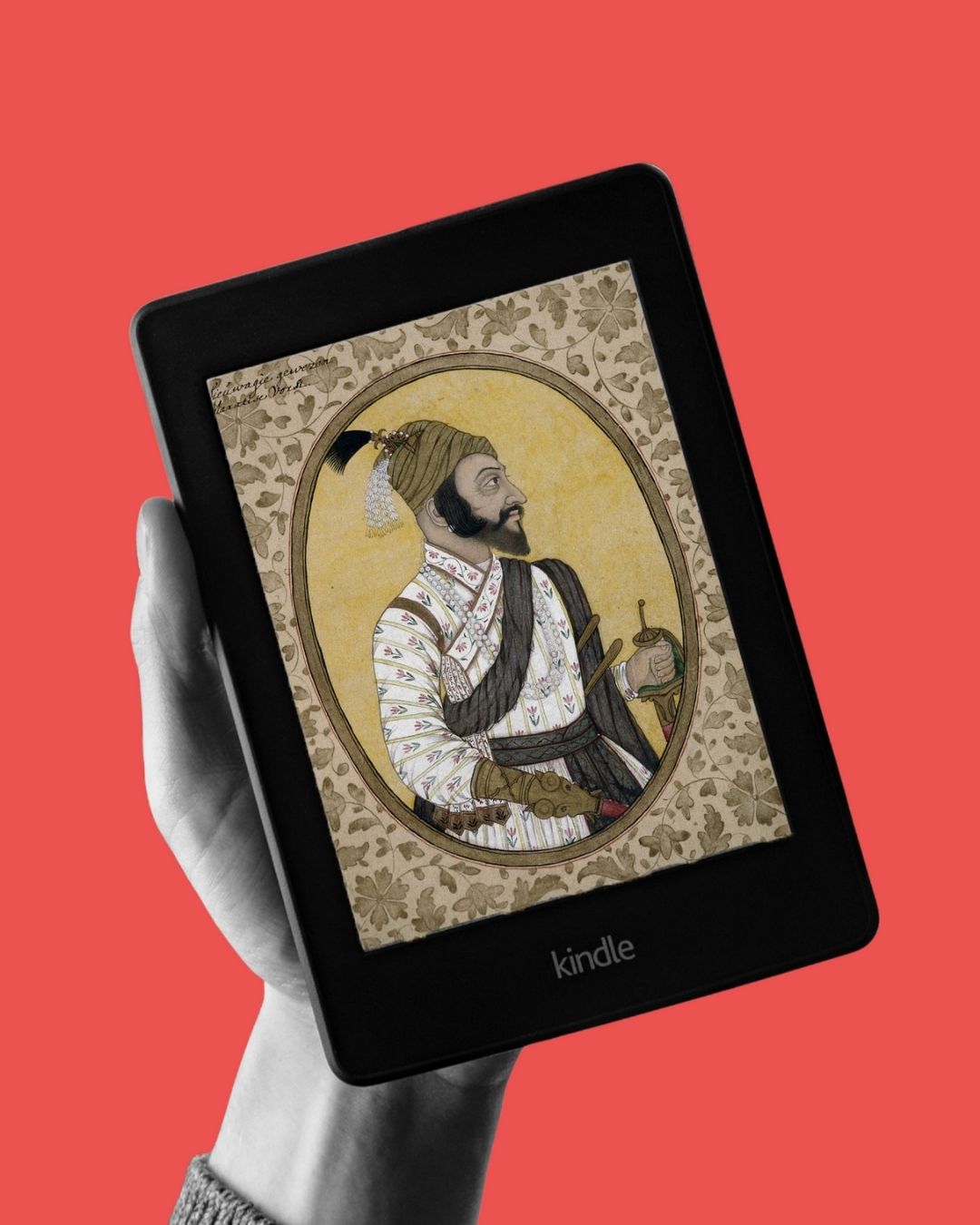

Unwrapping Dr. Ambedkar’s Quiet Gift to Ch. Shivaji Maharaj’s Legacy

By Nikhil Bagade

This sounds like a story that was almost lost to time, as we find little information of Dr. Ambedkar writing on Ch. Shivaji’s personal struggle, except in a few, but extremely important passages, dotted in his ocean of literature that has survived.

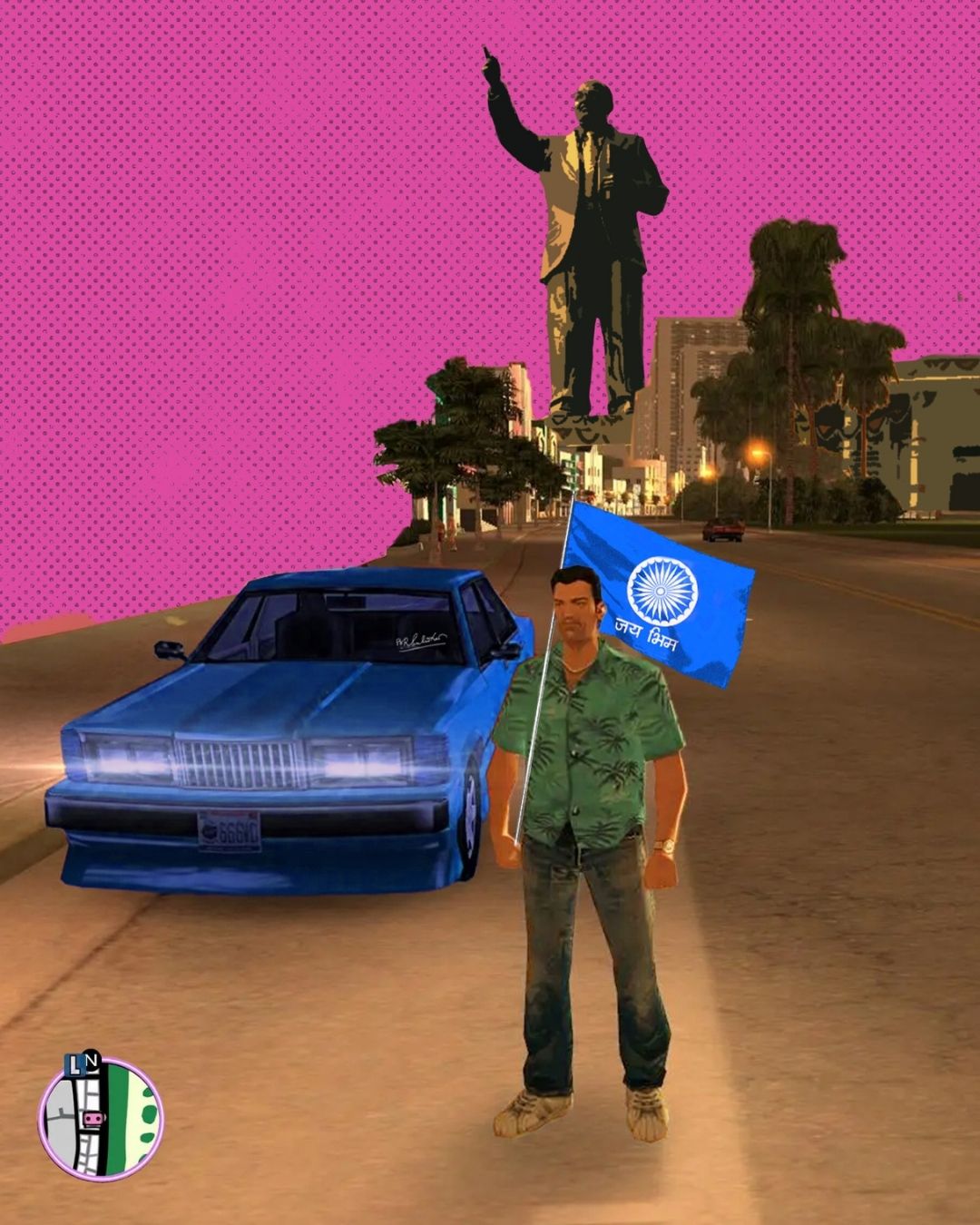

Debugging Inequality: Caste and Labour Hierarchies in Indian Gaming Industry

By Anonymous

It is of course in the best interest of the IT sector and the twice-borne castes who dominate it to represent the workplace as ‘casteless’, to maintain status quo, and leave the responsibility of addressing caste-inequality to the Government or the State.

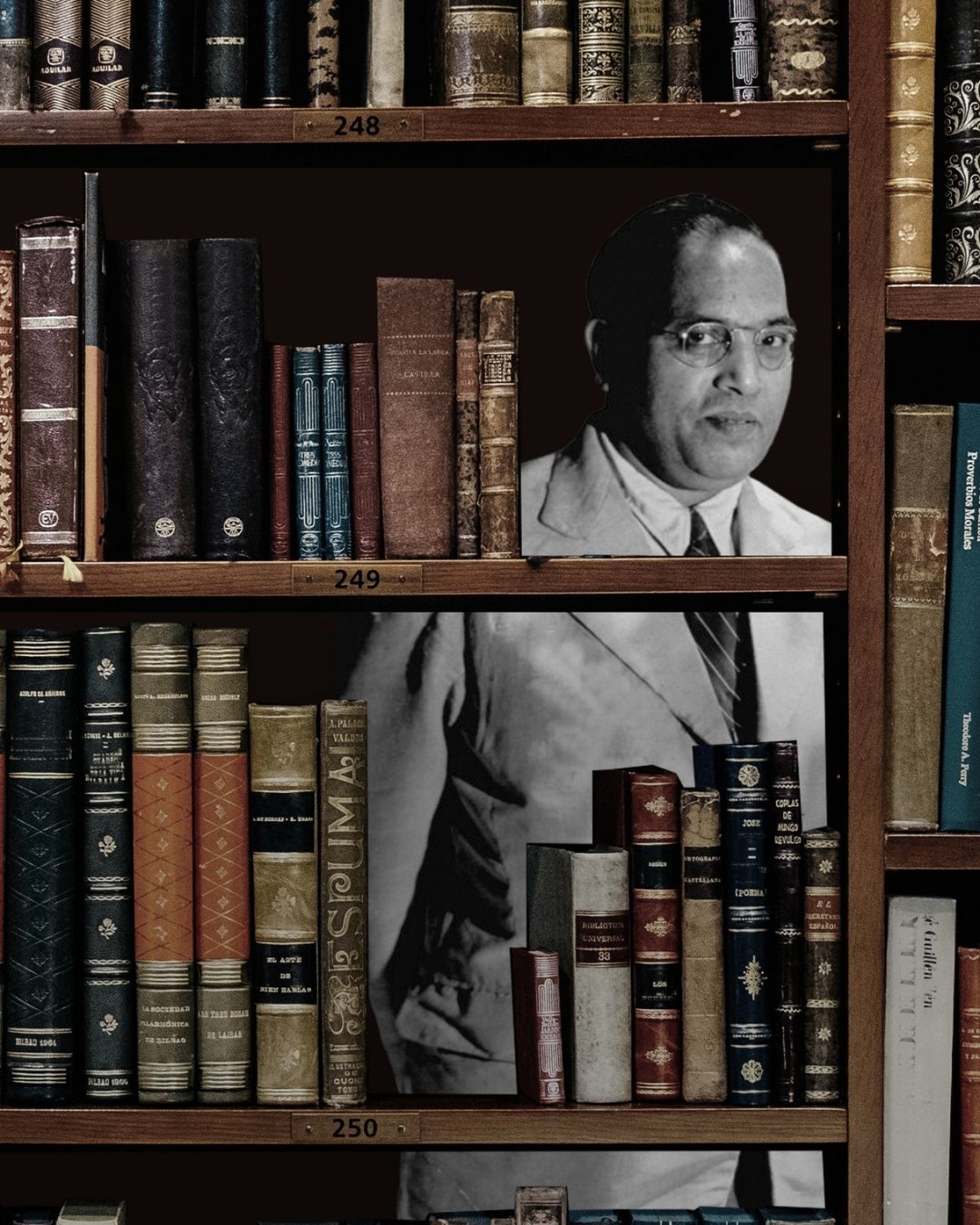

When Dr. Ambedkar Wrote to Maurice Dobb

By Nikhil Bagade

It is not a fanciful thought but a well-documented fact that whenever Dr. Ambedkar found himself in London, he would go shopping for books on various topics.

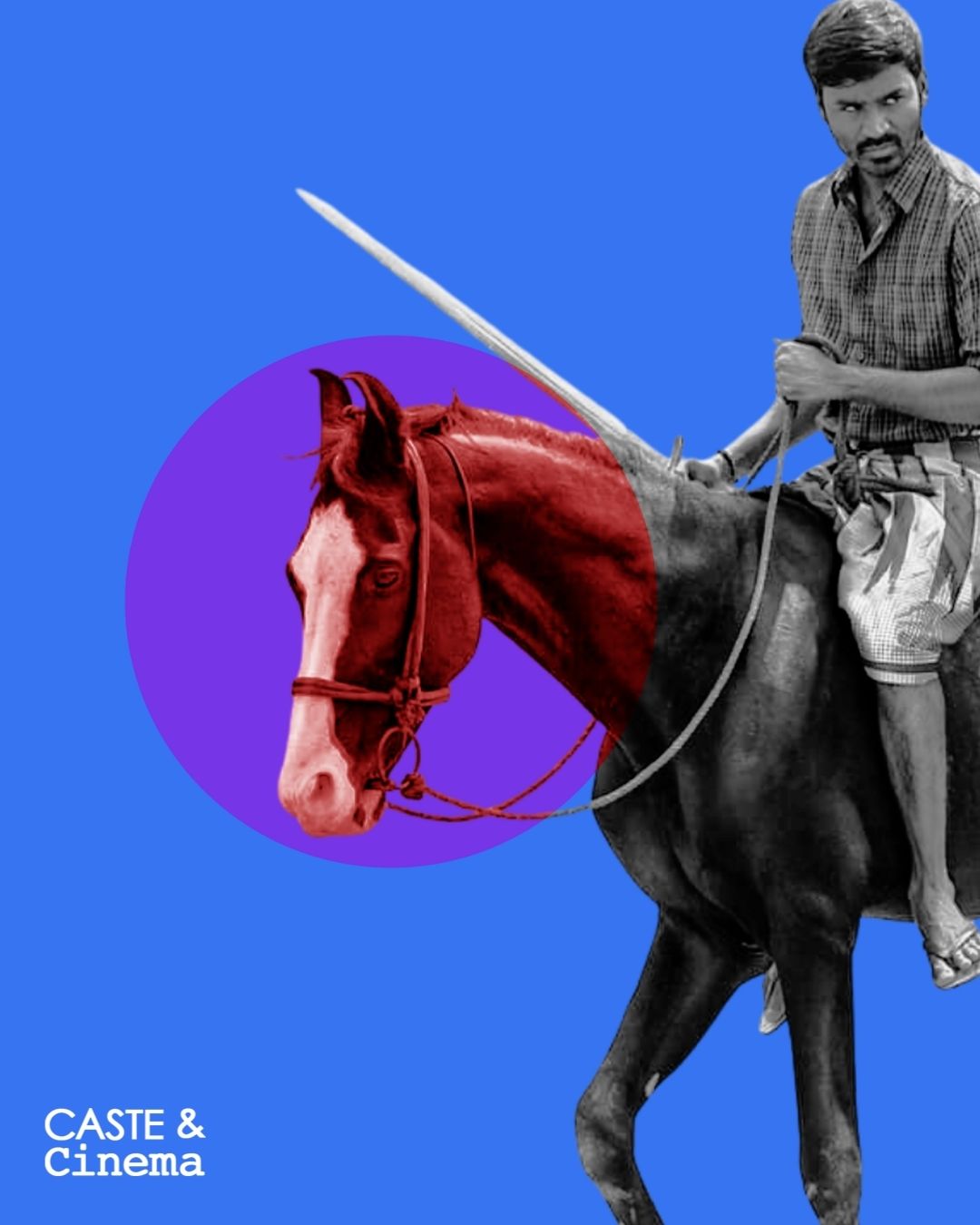

What Mari Selvaraj's Bison tells us about caste, sports and mobility in Tamil Society

By Roy Anto & Vignesh Shiva Subramaniam M

What kind of struggles a Dalit man has to face to achieve his dreams, and to break free from the shackles of caste? And what cost does he have to pay for this mobility?

The Spectacle of Humiliation: Notes on Caste, Academia, and the Left’s Betrayal

By Anshul Kumar

Humiliation is not merely an event; it is an experience that shapes the very structure of selfhood for the oppressed.

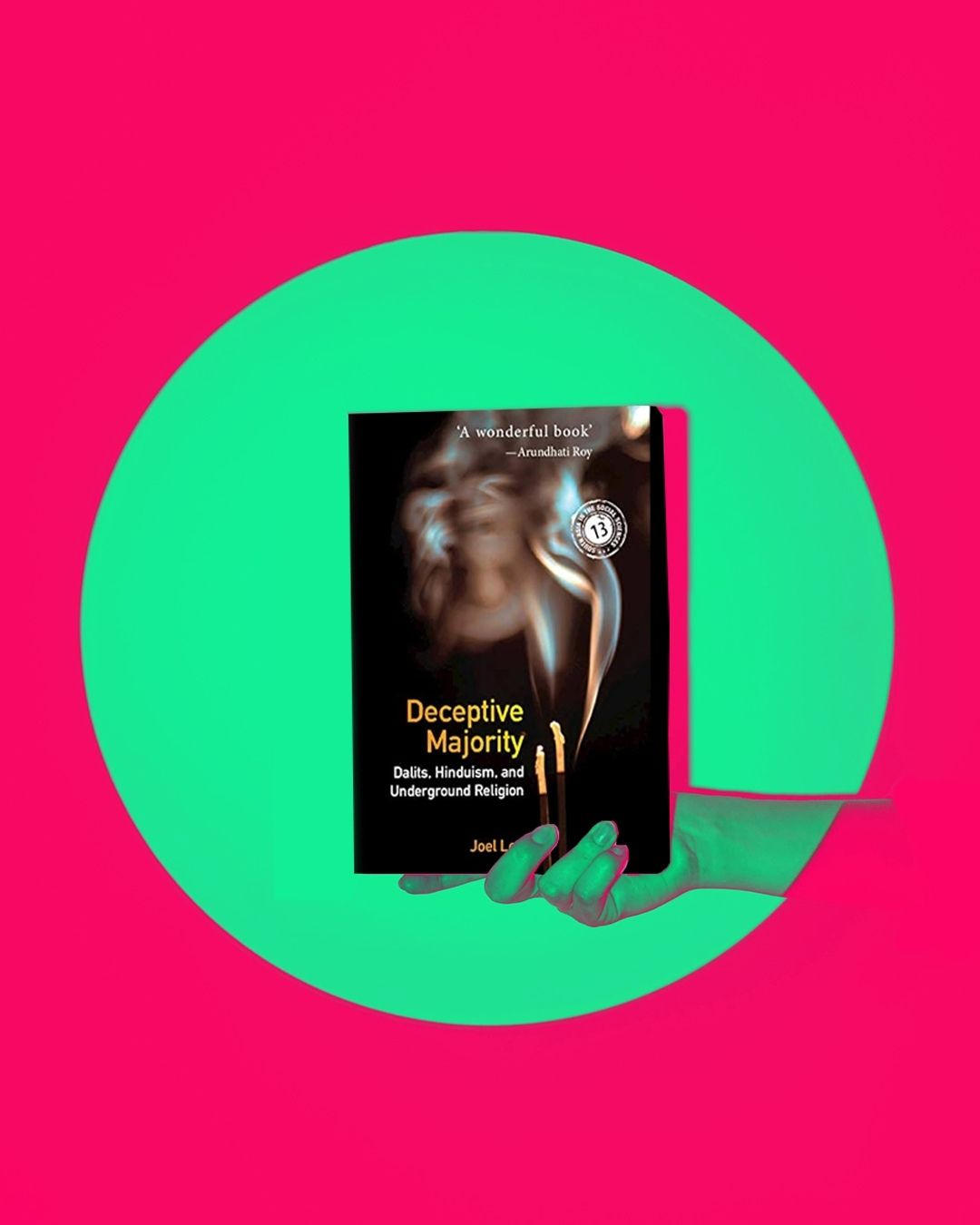

Book Synopsis and Sidenotes of Joel Lee’s Deceptive Majority Dalits, Hinduism, and Underground Religion (2021)

By Sumit Samos

Lee most importantly questions the Hindu-Muslim paradigm through which history and religion is largely understood in South Asia and brings in the discourse and self representation of Dalits that on many occasions runs counter to scholarly assumptions.

Hidden Hunger in Plain Sight: How Caste Gatekeepers Shape Food Insecurity Among Maharashtra's Marginalised

By Pritesh Dahiphale and Saumya Barmate

When fields are abundant yet plates remain empty, should we still call this hunger a matter of poverty or name it for what it is: a system designed to exclude?

Manusmriti, Bhimsmriti, and the Conscious Constitution: A Dalit at RSSs centenary celebration at Nagpur on Dussehra

By Shiva Thorat

The real question is not only which constitution we read but which one we live. Do we continue to inhabit the unconscious constitution of Manusmriti, reproducing hierarchy by habit, or do we consciously embrace the Ambedkarite constitution?

Bahujan India is the Real Young India

By Anand Kshirsagar

Recognising the true nature of Young India, which is ‘Bahujan India’, is not just a national obligation for India; it is a strategic imperative for the world. The prosperity of Bahujans is not a zero-sum outcome; it is the key to India’s shared and sustainable prosperity.

Love in the Time of Shame: on Failure, Survival, and Resistance

By Pranita Thorat

In school, we learn our first lesson in failure — not from textbooks, but from how we are seen: as children who lack something, as if we are incomplete. Children who face untouchability are told at every point that you lack merit, you don’t belong, or you are just not good enough.

A Ghost at the Banquet: On Being Excluded from Civil Society

By Athul Krishna

This is not a request for inclusion into your world as it exists. It is a demand to co-create a new one. A truly democratic society cannot be built first and then have accessibility bolted on as a charitable afterthought.

State sponsored shame: Navigating two selves as Dalit Christians

By Blessy

A Dalit Christian child is told to not tell anyone their religion as their religion and caste can not co-exist together –since being Christian is supposed to cancel out being Dalit. Our government names are hindu-ish, often with a separate Christian name for home and church. Two selves, from the moment of birth. We are never called by our government names at home.

The Legend of Bhadi Maay on the Banks of the Tapi River

By Shiva Thorat

The Mahar community on the banks of the Tapi River in Khandesh, Maharashtra cooks by shaping soldiers, fighter animals, and weapons from wheat. This is followed the next day by the cooking of red meat and sweets.

Our own Golem

By Aditya W

An exploration of the Golem of Prague as a political allegory for Bahujan politics, Kanshiram, and the current state of the Bahujan Samaj.

Revolt Without Revolution: The Unfulfilled Uprising in Nepal

By Dr. Rahul Sonpimple

Nepal’s youth revolt was not just against tyranny, but perhaps against the lack of it. A critical analysis of the uprising, the desire for a 'Strong Master,' and what it reveals about the state of democracy in South Asia.

I Brought Ambedkar Home: A Reflection of First-Generation Consciousness in Adopting Ambedkarism

By Preeti Koli

Being a first-generation Ambedkarite has never been theorised enough. This essay reflects on the complex journey of adopting Ambedkarism, navigating Dalit identity in academia, and forging a path that was never laid out before.

EVM “Vote chori”: Can our feudal democracy afford to move backward towards Ballot-Box democracy?

By Ritesh Jyoti

Replacing EVMs with ballot boxes seems like a simple fix, but it ignores a brutal history of violence, booth capturing, and caste terror. Can India's feudal democracy afford to go backward?

Communist capitalism is the future of capitalism, not an exception

By Dr. Rahul Sonpimple

The rise of China as a global superpower reveals an unsuspected truth: it’s not capitalists but communists who can run capitalism much better.

The Algorithm of Caste: Instagram Reels as a 'New' Site of Caste Reproduction and Reinforcement

By Roy Anto

Most of these reels invariably are tied to showcase the dominant caste supremacy, thereby triggering social division based on caste. The local caste politicians, caste party meetings and rallies, village festivals, or sometimes just a group of men enacting hypermasculinity through staged photographs with swords.

Kavin Selvaganesh's murder unearths ugly truths about caste

By Senan R

This murder is not one of its kind, it is an outcome of a deep-seated caste-based inequality materialised in the form of hatredness, sustained and perpetuated in the interest of endogamy/purity of one's caste.

Only a Free Woman Is a Muse.

By Hypatiaa

More importantly WHO was he? WHAT did he represent? Why are Indians so obsessed with his art a century later? Was he really that great an artist? Not really, to my eyes he seems like a hack. And most of the prominent art critics of the time saw him as an imitator of Western Aesthetics. A mimic. So WHY is he so desperately beloved of Indians?

Inherited Pain: How sickle cell reveals the intergenerational violence of caste

By Saumya Barmate

The annihilation of caste is not an ideal. It is the only cure.

20 years of 26 July.

By Shripad Sinnakaar

Now back to that afternoon of 26th July, 2005. I remember waking up to the water cascading in from both sides of the door, since the ledges resisted the stream, the flood hit them from the inside in an upstream, making the flood look like a fountain...

Trapped In Cynicism: The Post-Ideological Liberal’s Opposition and the Everyday of India’s Right Wing

By Dr. Rahul Sonpimple

The liberal does not wish to engage with the forces that produce majoritarian sentiment; rather, they perform their distance from it...

Response to Professor Yogendra Yadav: Ambedkar, Iconization, and The Burden of Radicality

By Sumit Samos

Iconization of Ambedkar Vs Gandhi—Different Histories, Different Stakes

Spontaneity in Ambedkar: Beyond the Passivity of Popular Dalit Discourse.

By Dr. Rahul Sonpimple

Ambedkar did not trust time; he trusted action.

WHEN THE EARTH BURNS, WHO GETS BURIED FIRST?

Climate change is not casteless. In India, caste decides who lives on the margins of survival. As the planet heats, Dalit and Adivasi communities face the harshest consequences.

Caste and Climate Change

"If God is Dead, Everything is Permitted", Dostoevsky's dictum can have several meanings.

But in Brahminism, everything is permitted under the divinity of gods, from inhumanity to obscenity, everything is sanctified...

Caste in Temple

Merit, Bias, and Belonging: The Silent Battle Against Caste in Universities

Caste on Campus: Part 01

Caste on Campus: Part 02

Archives