Dhammachakka pavatan through the history

Dikshita Jadhav

Dhammachakkapavatan Dīn (October 14, 1956) is a landmark date in Indian history, commemorating the occasion when Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, along with thousands of his followers, converted to Buddhism in Deekshabhoomi, Nagpur. This act of mass conversion marked a significant cultural and religious transformation, particularly for individuals from oppressed castes seeking to escape the entrenched inequalities of the caste system in Hindu society. Since that historic day, every year on October 14, many individuals continue to follow Dr. Ambedkar’s path, organising mass conversion ceremonies across various regions in India. The act of conversion is not merely a change of religion; it is a profound statement against social discrimination and a quest for dignity and equality. In 2022, the political ramifications of this act were highlighted when Rajendra Pal Gautam, a dalit minister from the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), resigned following his participation in a mass conversion ceremony in Karol Bagh, New Delhi. His resignation underscores the tensions surrounding the act of conversion, especially as it challenges the dominant caste’s authority.

To understand why the conversion to Buddhism poses a threat to dominant caste leaders, it is essential to explore the historical significance of religious conversion and its implications for social structures. The aṣṭamahāpratihārya, or the great eight episodes, provides a comprehensive overview of the life of the Buddha. Key events in his life include his birth into royalty, shielding him from the realities of suffering, and his attainment of enlightenment under the Bodhi tree after years of ascetic practice, realising the nature of suffering and the path to liberation. Upon his enlightenment, Buddha delivered his first sermon at Sarnath, setting the Dhammacakka (the wheel of dhamma) in motion. In this sermon, he articulated the Four Noble Truths and introduced the Middle Path as a means to transcend suffering, which was then recorded in the sutta. Throughout his life, the Buddha performed various miracles, including the taming of Nalagiri, the elephant, and the miracle at Sravasti which reinforced his teachings and attracted followers.

While the narrative of Dhammachakkapavatan Dīn is often associated with Emperor Ashoka, numerous historical figures were instrumental in espousing Buddhism in its earlier days. Bimbisara, the King of Magadha, met the Buddha and became one of his earliest followers, providing crucial patronage that allowed Buddhism to flourish during its formative years. Ajatashatru, the son of Bimbisara, was a contemporary of the Buddha and accepted his teachings, playing a significant role in organising the First Buddhist Council at Rajgir, which helped consolidate the Buddha’s teachings. Pasenadi, the King of Kosala, was also a prominent supporter. He invited Buddha to his capital Shravasti where the Buddha performed notable miracles and delivered teachings. Pasenadi commissioned numerous stupas which further embedded Buddhism within the cultural landscape of the region.

The Kushan Empire (c. 30–375 CE) marked a transformative period for Buddhism, particularly through its interactions along the Silk Route. The Kushan rulers, especially Kanishka the Great, were significant patrons of Buddhism, facilitating its spread across Asia and encouraging cross-cultural exchanges. This era also saw the emergence of Gandhara art, a unique blend of Greek artistic influences and Buddhist themes, which played a crucial role in the visual representation and dissemination of Buddhist teachings.

The legacy of Dhammachakkapavatan Dīn resonates deeply within contemporary Indian society. Dr. Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism represents not only a rejection of caste hierarchies inherent in Hinduism but also a powerful assertion of identity and dignity for bahujans. The historical connections between early Buddhist kings, their support for the Buddha, and the ongoing impact of Buddhism highlight its enduring relevance. As we reflect on these events, we recognize that the struggle for equality and justice continues, underscoring the transformative potential of Buddhism as a path toward social change.

Historical records suggest that the Buddha lived during the Mahajanapada period, a time when sixteen kingdoms existed in ancient India during the second urbanisation when iron tools started emerging. Although the exact dates of his birth and death remain uncertain, there are accounts of his age and notable contemporary figures. Records indicate that he attained enlightenment at the age of 35 in Bodh Gaya and passed away at 80 in Kushinagara. Over the 45 years following his enlightenment, the Buddha travelled extensively across various kingdoms, spreading his teachings far and wide.

According to the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta, after his death in Kushinagara, the Mallas of Kushinagara cremated his body, sparking a dispute over his relics among the Mallas, the Shakyas (Buddha’s clan), and six other kingdoms. The eight parties involved were: Ajātasattu, king of Magadha; the Licchavis of Vesāli; the Sakyas of Kapilavastu; the Bullis of Allakappa; the Koliyas of Rāmagāma; a Brahmin from Veṭhadīpa; the Mallas of Pāvā; and the Mallas of Kusinārā. The Buddha’s dhamma was practised in these kingdoms as it challenged the prevailing religious order and rejected the authority of the Vedas.

Historical records show that ten stupas were initially constructed to house the Buddha’s relics, nine of which were later reopened by Emperor Ashoka to redistribute the relics across Asia. Ashoka’s edicts, along with texts such as the 2nd-century Aśokāvadāna, the Sri Lankan chronicle Mahavamsa, and the Aśokāvadāna (translated into Chinese by Fa Hien) mention the construction of 84,000 stupas, viharas, and caves throughout Asia. The legend of the Great Ten Stupas was corroborated by archaeological discoveries in the 1890s including the Ashokan pillar at Lumbini which confirmed the Buddha’s birthplace.

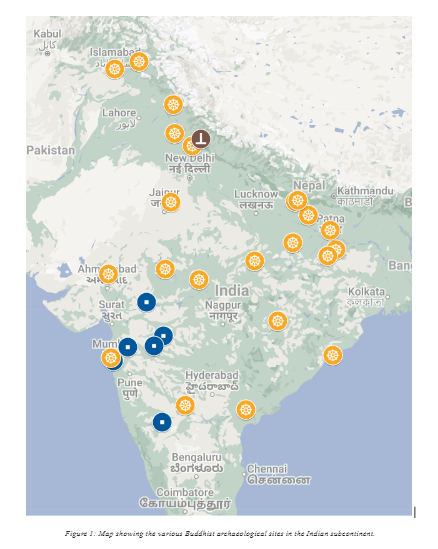

In 1898, William C. Peppé excavated a mound in present-day Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, where he discovered a coffer containing a casket inscribed in Brahmi script. The inscription read, “Sukiti bhatinam sa-bhaginikanam sa-puta-dalanam iyam salila nidhare Bhaddhasa bhagavate sakiyanam,” meaning, “This noble deed of depositing Buddha’s relics was carried out by the brothers, sisters, and children of the Sakyas.” This find helped to identify the ancient city of Kapilavastu and the other nine great stupas. However, the spread of Buddhism extended much further, as evidenced by Buddhist architecture found as far afield as Afghanistan in the Northwest, Assam, and the caves of the Western Ghats and Karnataka, some of which are noted on the adjoining map.

Caves:

- Ajanta Caves

- Ellora Caves

- Kanheri Caves

- Pandav Leni Caves

- Bagh Buddhist Caves

- Badami Cave Temples

Stupa

- Chetru, HP

- Ushkar, Kashmir

- Sanghol, Punjab

- Kanaganahalli, Karnataka

- Rajgir, Bihar

- Sarnath, UP

- Piprahawa, UP

- Kapilavastu, Nepal

- Chaneti, Haryana

- Vaishali, Bihar

- Udayagiri, Odisha

- Bairat, Rajasthan

- Kolvi, Rajasthan

- Vadanagr, Gujrat

- Amaravati Stupam, Andhra Pradesh

- Lumbini, Nepal

- Bhamala Stupa, Pakistan

- Sanchi Stupa, MP

- Sirpur, Chattisgarh

- Bodhgaya, Bihar

- Sopara Stupa, Maharastra

- Bharhut Stupa, MP

Edict

- Kalsi Asoka Edict

The distribution of Buddhist sites across the subcontinent illustrates the rapid spread of the Dhamma. Inscriptions show that donors came from all levels of society, including both the common people and the merchant or ruling classes. Buddhism’s teachings were widely embraced across different kingdoms because of their simplicity making them accessible and presenting a potential challenge to Brahmanism.

On October 14 1956, when Dr. Ambedkar, along with hundreds of thousands of followers renounced Hinduism and embraced the teachings of the Buddha He was following in the footsteps of many before him—a path toward equality, end of oppression, and upliftment of the masses. Seven decades later, and thousands of years after the Buddha’s enlightenment, his light continues to shine brightly, illuminating the path for the dhamma and sangha.

Dikshita Jadhav

Dikshita Jadhav graduated with a background in History and Sociology and is currently pursuing an MA in History of Art from the Indian Institute of Heritage (formerly the National Museum Institute). With work experience at the National Museum, New Delhi, her area of expertise focuses on Buddhist Art and History.

Date: 15 - 10 - 2024